The birth of the Fascist movement can be traced to a meeting he held in the Piazza San Sepolcho in Milan Italy on March 23, 1919. This meeting declared the original principles of the Fascists through a series of declarations.

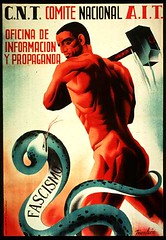

Anti-fascist Spanish poster.

Fascism is an authoritarian political ideology (generally tied to a mass movement) that considers individual and other societal interests subordinate to the needs of the state, and seeks to forge a type of national unity, usually based on ethnic, cultural, or racial attributes. Various scholars attribute different characteristics to fascism, but the following elements are usually seen as its integral parts: nationalism, authoritarianism, militarism, totalitarianism, anti-communism and opposition to economic and political liberalism.

The governments most often considered to have been fascist include the Mussolini government in Italy, which invented the word; Nazi Germany under Adolf Hitler, but other similar movements existed across Europe in the 1920s and 1930s.

Fascism and the avant-garde

Fascism attracted political support from diverse sectors of the population but most surprisingly also from intellectuals and artists such as Gabriele D’Annunzio, Curzio Malaparte, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Knut Hamsun, Ernst Jünger, Wyndham Lewis, Ezra Pound, and Martin Heidegger.

Ze’ev Sternhell (The Birth of Fascist Ideology (1989)) argues that European fascism first articulated itself as a cultural phenomenon, as a nonconformist, avant-garde, revolutionary movement. Modernism, says John Carey in The Intellectuals and the Masses (1992), is a literary theory of fascism.

Manifesto of the Fascist Intellectuals

The Manifesto of Fascist Intellectuals was written during the course of the Conference of Fascist Culture, held in Bologna, Italy, on March 29 and 30, 1925. It was published a few weeks later in nearly all Italian newspapers on April 21, by tradition the anniversary of the Founding of Rome. The secretary to the conference told the Italian news media that over 400 intellectuals attended the meeting; however, the number who gave public support to the manifesto was only 250, among them Vittorio Cian, Francesco Ercole, Curzio Malaparte, Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Ernesto Murolo, Ugo Ojetti, Alfredo Panzini, Ardengo Soffici, Lionello Venturi, Gioacchino Volpe, and Giuseppe Ungaretti. Luigi Pirandello, though not present at the conference, announced his support of the manifesto by letter. Support for the manifesto by Neopolitan poet Salvatore Di Giacomo resulted in a falling out with Benedetto Croce, who, shortly afterwards, responded to the Fascist proclamation with his own Manifesto of the Anti-Fascist Intellectuals.

Fascism in fiction:

Christ Stopped at Eboli

Carlo Levi was a painter and writer, but he also had a degree in medicine. Arrested in 1935 by Mussolini’s regime for his anti-Fascist activities, he was sent to live in remote town in southern Italy, in the region of Lucania which is known today as Basilicata. The landscape was beautiful, the peasantry poor and neglected. Since the local doctors were not interested in peasants and not trusted by them, he began to help them.

A Special Day

As her entire family (including her fascist husband) goes to the streets to follow Hitler‘s visit to Mussolini in Rome, an Italian housewife (Sophia Loren) stays home looking after some domestic tasks. Her apartment building is empty but for a man (Marcello Mastroianni) who seems repulsed by fascism (a strange attitude in those days).

The audience learns early in the movie that this man is a radio broadcaster who has lost his job and is about to be deported due to his political attitudes and his homosexuality. Unaware of this, the housewife flirts with him, as they meet by chance (or intentionally) in the empty building. During their conversation, the rather naïve and mainstream woman is surprised by his opinions and finally shocked when she realizes his sexual orientation.

Nonetheless, despite their fights and arguments, they eventually make love before he is taken away by the police and her family comes back home.

Further reading

- The Mass Psychology of Fascism (1933) by Wilhelm Reich

- The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951) by Hannah Arendt

- Fascinating Fascism (1975), an essay by Susan Sontag

- Sex Drives: Fantasies of Fascism in Literary Modernism (2002) by Catherine Laura Frost

- The Seduction of Unreason (2004) by Richard Wolin