A couple of weeks ago, I got up at five in the morning to be interviewed by Annemie Tweepenninckx in her radio show Bar du Matin.

Detail from Rubens’s Three Graces, the most iconic of Rubenesque women

The occasion was the exhibition Sensation and Sensuality – Rubens and His Legacy. I had been asked to explain my stance (first voiced in my book The History of Erotica) that the female beauty ideal of the 17th century was perhaps not the Rubenesque woman, but rather that the Rubenesque woman was a personal fetish of Rubens.

In preparing for the radio show I first phoned the Rubenshuis asking if someone wanted to comment on my position. The representative of the Rubenshuis said a Rubens expert would get back to me. As I sensed when hanging up, this has not happened until today.

Online research led to the discovery of a new paper: Defining beauty: Rubens’s female nudes by Dutch scholar Karolien De Clippel. Her paper includes “De Forma Foeminea“, a section from Peter Paul Rubens’s notebooks. It is in this section that Rubens tellingly compares woman to … a horse, “the most noble and elegant amongst animals”.

I wrote an email to Mrs. De Clippel asking her what she thought of the Rubenesque question. In her answer, De Clippel takes the middle position, stating that the Rubenesque woman is an “artistic beauty ideal” (rather than a plain “beauty ideal”) born from Rubens’s desire to emulate. This, she says, “brings him to his type of ladies, very idiosyncratic.” She adds that “Titian’s women too were very voluminous, but because of the less lifelike depiction of skin and flesh, these seem less full but if you would measure them you would get the same proportions as in Rubens.”

I’m not convinced by Mrs. De Clippel’s arguments.

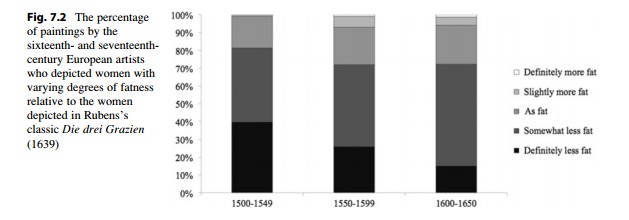

Than I remembered research by Devendra Singh I first stumbled upon in 2011. In this research, “independent judges compared European paintings from 1500-1650 with Rubens’ paintings to determine whether other artists painted women as fat or fatter than those in Rubens’ depictions. Results showed that the preponderance of Baroque artists did not share Rubens’ inclination to paint heavy women.”

So I wrote to the University of Texas to find out more about this research. I managed to get in touch with Jaime M. Cloud who sent me his chapter “Bodily Attractiveness as a Window to Women’s Fertility and Reproductive Value” (2014), a text by himself and Carin Perilloux (dedicated to the memory of Devendra Singh) and which features the result of “Singh’s research into the Rubenesque“.

In Jaime M. Cloud’s chapter is Figure 7.2 (above) which “presents the percentages of paintings depicting women with varying degrees of fatness relative to the women depicted in Die drei Grazien (ranging from definitely less fat to definitely more fat). For each 50-year interval between 1500 and 1650, the majority of artists depicted women as less fat than those in Die drei Grazien. These findings indicate that like Picasso’s (1881–1973) unusual depictions of the human form, Rubens portrayed atypical characterizations of women for the Baroque era. The fact that the preponderance of Baroque artists did not idealize a female figure as considerably different from the figure preferred today calls into question the most prevalent example for the argument that standards of beauty are culturally defined.”

I was thrilled with this paragraph and wanted to know more. Specifically, I hoped to find out about the sample paintings and the methodology. Who, for example, were the Baroque artists?

So again I wrote to Jaime M. Cloud.

Sadly, he informed me that the information in his chapter is all there is of the research. In the words of Jaime M. Cloud: “Singh was largely responsible for designing the study and collecting the data; after he passed, I lost access to much of that information (although his daughters might be able to access it). I simply wrote up his results.”

Maybe one day I will contact Singh’s daughters, of whom Jaime M. Cloud gave me the names.

For now, I’m going to leave the data in limbo.

![The buttocks and bellies of The Three Graces by Peter Paul Rubens. <br />

The Three Graces is held as the most rubenesque of all Rubens’s paintings.<br />

This post accompanies a post at the Macroblog[1].](http://33.media.tumblr.com/97423d08593625713193344b7db59941/tumblr_ne4k67g1qZ1qz4yqio1_250.jpg)