Futurism @100

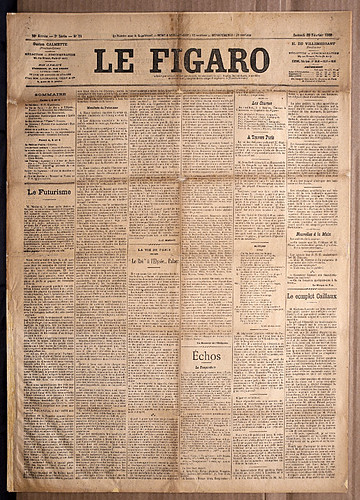

Tomorrow, February 20, 1909, it will have been 100 years since the Futurist Manifesto was published in the French conservative newspaper Le Figaro.

Futurism is now known as a early 20th century avant-garde art movement focused on speed, the mechanical, and the modern, which took a deeply antagonistic attitude to traditional artistic conventions.

Centrale elettrica (1914) – Antonio Sant’Elia

The Futurists explored every medium of art, including painting, sculpture, poetry, theatre, music, architecture and even gastronomy. The Italian poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti was the first among them to produce a manifesto of their artistic philosophy in his Manifesto of Futurism (1909), first released in Milan and published in the French paper Le Figaro (February 20). Marinetti summed up the major principles of the Futurists, including a passionate loathing of ideas from the past, especially political and artistic traditions. He and others also espoused a love of speed, technology and violence. The car, the plane, the industrial town were all legendary for the Futurists, because they represented the technological triumph of man over nature.

Photograph of intonarumori: “intoners” or “noise machines”, built by Russolo, mostly percussion, to create “noises” for performances. Unfortunately, none of his original intonarumori survived World War II.

Marinetti’s impassioned polemic immediately attracted the support of the young Milanese painters —Boccioni, Carrà, and Russolo—who wanted to extend Marinetti’s ideas to the visual arts (Russolo was also a composer, and introduced Futurist ideas into his compositions). The painters Balla and Severini met Marinetti in 1910 and together these artists represented Futurism’s first phase.

Mina Loy (1909), photo by Stephen Haweis

Futurism’s misogyny is illustrated by article 9 (below): we will glorify scorn of woman

It was one of the few art movements to be initiated by a manifesto.

In fact, manifestos were introduced with the Futurists (not entirely true, there were the Symbolists and the Decadents with their manifestos) and later taken up by the Vorticists, Dadaists and the Surrealists: the period up to World War II created what are still the best known manifestos. Although they never stopped being issued, other media such as the growth of broadcasting tended to sideline such declarations.

Full text of the manifesto

- We intend to sing the love of danger, the habit of energy and fearlessness.

- Courage, audacity, and revolt will be essential elements of our poetry.

- Up to now literature has exalted a pensive immobility, ecstasy, and sleep. We intend to exalt aggressive action, a feverish insomnia, the racer’s stride, the mortal leap, the punch and the slap.

- We affirm that the world’s magnificence has been enriched by a new beauty: the beauty of speed. A racing car whose hood is adorned with great pipes, like serpents of explosive breath—a roaring car that seems to ride on grapeshot is more beautiful than the Victory of Samothrace.

- We want to hymn the man at the wheel, who hurls the lance of his spirit across the Earth, along the circle of its orbit.

- The poet must spend himself with ardor, splendor, and generosity, to swell the enthusiastic fervor of the primordial elements.

- Except in struggle, there is no more beauty. No work without an aggressive character can be a masterpiece. Poetry must be conceived as a violent attack on unknown forces, to reduce and prostrate them before man.

- We stand on the last promontory of the centuries!… Why should we look back, when what we want is to break down the mysterious doors of the Impossible? Time and Space died yesterday. We already live in the absolute, because we have created eternal, omnipresent speed.

- We will glorify war—the world’s only hygiene—militarism, patriotism, the destructive gesture of freedom-bringers, beautiful ideas worth dying for, and scorn for woman.

- We will destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind, will fight moralism, feminism, every opportunistic or utilitarian cowardice.

- We will sing of great crowds excited by work, by pleasure, and by riot; we will sing of the multicolored, polyphonic tides of revolution in the modern capitals; we will sing of the vibrant nightly fervor of arsenals and shipyards blazing with violent electric moons; greedy railway stations that devour smoke-plumed serpents; factories hung on clouds by the crooked lines of their smoke; bridges that stride the rivers like giant gymnasts, flashing in the sun with a glitter of knives; adventurous steamers that sniff the horizon; deep-chested locomotives whose wheels paw the tracks like the hooves of enormous steel horses bridled by tubing; and the sleek flight of planes whose propellers chatter in the wind like banners and seem to cheer like an enthusiastic crowd.

Interesting to know that the manifesto was originally published in a conservative journal. I think a lot of the Futurists went on to join the Italian Fascists, though some died in WWI, gloriously, no doubt.

Off topic, except for the link between machines and art, found experiences, etc, you and your readers might find this post and the links amusing – subways humming West Side Story:

http://iamyouasheisme.wordpress.com/2009/02/21/i-am-not-crazy/