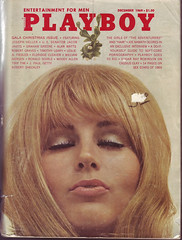

Playboy magazine, December 1969 in which Cross the Border — Close the Gap was first published in English.

Cross the Border — Close the Gap (1968) is a nobrow treatise on postmodern tendencies in literature by American literary critic Leslie Fiedler.

The treatise coincides with a trend in which literary critics such as Leslie Fiedler and Susan Sontag started questioning and assessing the notion of the perceived gap between “high art” (or “serious literature“) and “popular art” (in America often referred to as “pulp fiction“), in order to describe the new literature by authors such as John Barth, Leonard Cohen , and Norman Mailer; and at the same time re-assess maligned genres such as science fiction, the western, erotic literature and all the other subgenres that previously had not been considered as “high art”, and their inclusion in the literary canon:

- The notion of one art for the ‘cultural,’ i.e., the favored few in any given society and of another subart for the ‘uncultured,’ i.e., an excluded majority as deficient in Gutenberg skills as they are untutored in ‘taste,’ in fact represents the last survival in mass industrial societies (capitalist, socialist, communist — it makes no difference in this regard) of an invidious distinction proper only to a class-structured community. Precisely because it carries on, as it has carried on ever since the middle of the eighteenth century, a war against that anachronistic survival, Pop Art is, whatever its overt politics, subversive: a threat to all hierarchies insofar as it is hostile to order and ordering in its own realm. What the final intrusion of Pop into the citadels of High Art provides, therefore, for the critic is the exhilarating new possibility of making judgments about the ‘goodness’ and ‘badness’ of art quite separated from distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ with their concealed class bias.

In other words, it was now up to the literary critics to devise criteria with which they would then be able to assess any new literature along the lines of “good” or “bad” rather than “high” versus “popular”.

Accordingly,

- A conventionally written and dull novel about, say, a “fallen woman” could be ranked lower than a terrifying vision of the future full of action and suspense.

- A story about industrial relations in the United Kingdom in the early 20th century — a novel about shocking working conditions, trade unionists, strikers and scabs — need not be more acceptable subject-matter per se than a well-crafted and fast-paced thriller about modern life.

But, according to Fiedler, it was also up to the critics to reassess already existing literature. In the case of U.S. crime fiction, writers that so far had been regarded as the authors of nothing but “pulp fiction” — Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett, James M. Cain, and others — were gradually seen in a new light. Today, Chandler’s creation, private eye Philip Marlowe — who appears, for example, in his novels The Big Sleep (1939) and Farewell, My Lovely (1940) — has achieved cult status and has also been made the topic of literary seminars at universities round the world, whereas on first publication Chandler’s novels were seen as little more than cheap entertainment for the uneducated masses.

Nonetheless, “murder stories” such as Dostoyevsky‘s Crime and Punishment or Shakespeare‘s Macbeth are not dependent on their honorary membership in this genre for their acclaim.

P.S. This article is based on freely available Wikipedia code remixed by myself for the Art and Popular Culture wiki.

Pingback: Nobrow manifesto #3 « Jahsonic