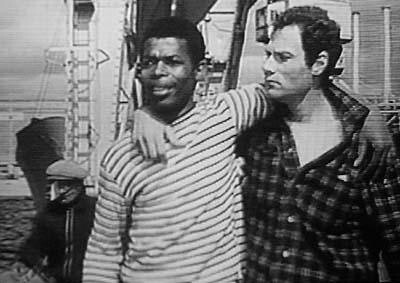

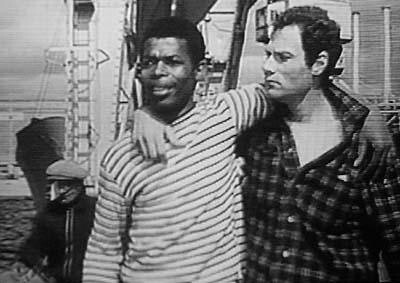

I Spit On Your Grave (1959) – Michel Gast

On the morning of this date in 1959, Boris Vian was at the Cinema Marbeuf in Paris for the screening of the film version (see picture above) of his controversial “Vernon Sullivan” novel, I Spit On Your Graves. He had already fought with the producers over their interpretation of his work and he publicly denounced the film stating that he wished to have his name removed from the credits. A few minutes after the film began, he reportedly blurted out: “These guys are supposed to be American? My ass!” He then collapsed into his seat and died of a heart attack en route to the hospital.

Background:

J’irai cracher sur vos tombes (Eng: I Spit On Your Graves) is a 1946 French language novel by Boris Vian written under the pseudonym Vernon Sullivan. It was adapted to film by Michel Gast in 1959. Radley Metzger bought the American the rights to this film and distributed it there from 1963 onwards. Miscegenation, murder and revenge are the themes of this French crime drama set in the American south.

Plot

The story, like the other stories that Vian wrote under the “Sullivan” moniker, is set in the American South and describes the difficulties African Americans face in their daily lives with “whites”. In this novel, Lee Anderson, a light-skinned African-American, leaves his native town after his brother was lynched and hanged because he was in love with a white woman. Once arrived in this other city, Lee becomes librarian and fraternizes with the local youngsters who crave for alcohol and sex. His goal is to avenge his brother.

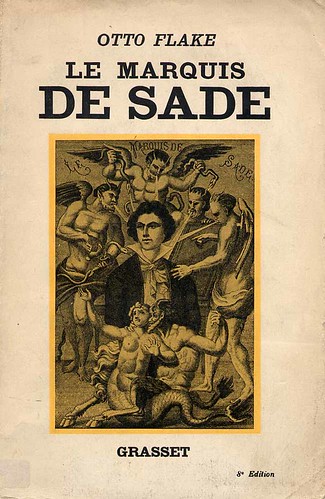

Different in style from other Vian novels, this story is more violent, rawer and most representative of the “Sullivan” series, in which Vian denounces the atmosphere of racism and the precarious situation of African Americans’ living conditions in the American South.

Shortly after its publication (in 1949) the novel was banned because it was perceived as pornographic and immoral; Vian himself was convicted of “outrage aux bonnes mœurs” [2] a French phrase meaning outrage to public morality or “an insult to public decency. (see Censorship in France) There was a 1947 illustrated version by Jean Boullet. The novel also exists in a bowlderized version.

I’ve previously written about Vian here.