Prompted by my previous post on Nietzsche in film, here is an interesting film on the life of Immanuel Kant, more particularly on his last days.

The film, Les Derniers Jours d’Emmanuel Kant is based on The Last Days of Immanuel Kant by English writer Thomas De Quincey.

In the film, Kant approaches the end of his life, which is entirely punctuated by habits acquired over many years. The leaving of his butler Martin Lampe will upset this well planned routine.

In the scene above, Kant reads a letter asking for help. It is a letter by Maria von Herbert, sent in August 1791.

The letter was also mentioned in La vie sexuelle d’Emmanuel Kant, about which I have written here.

Like so many philosophers, Kant was not sexually active. For all we know, Immanuel Kant died a virgin. I find this very interesting.

So did Friedrich Nietzsche, in The Genealogy of Morals he says on married philosophers:

- “the philosopher shudders mortally at marriage, together with all that could persuade him to it—marriage as a fatal hindrance on the way to the optimum. Up to the present what great philosophers have been married? Heracleitus, Plato,Descartes, Spinoza, Leibnitz, Kant, Schopenhauer—they were not married, and, further, one cannot imagine them as married. A married philosopher belongs to comedy, that is my rule; as for that exception of a Socrates—the malicious Socrates married himself [to Xanthippe], it seems, ironice, just to prove this very rule.”

So did Jacques Derrida.

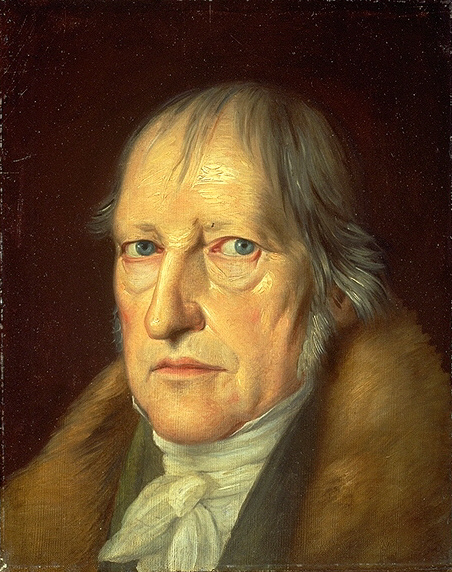

- Asked what would he like to see in a documentary on a major philosopher, such as Hegel or Heidegger, Derrida replies he would want them to speak of their sexuality and ‘the part that love plays in their life’. He criticizes the dissimulation of such philosophers concerning their sex lives – ‘why have they erased their private life from their work?’

_is_an_oil_on_canvas_(26x19cm)_painted_by_Antoine_Watteau.jpg)