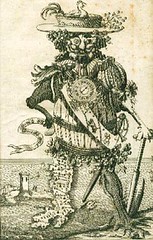

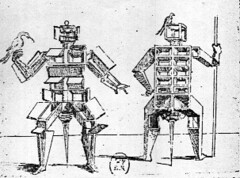

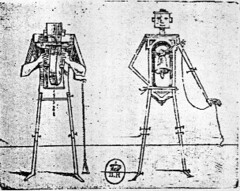

André Martins de Barros more here, Barros is also the artist who did the flyer I first encountered on Ian McCormick’s grotesque page.

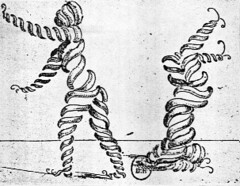

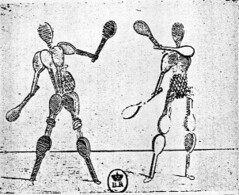

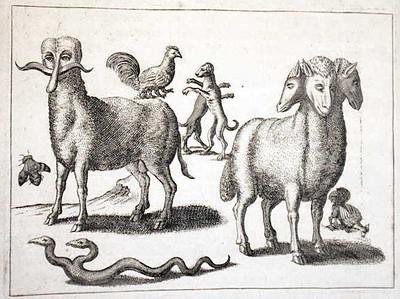

Found when Googling for Arcimboldesque, this anomymous etching c.1700, mid-Italian map, sourced here

The Moviegoer is a 1961 Kierkegaardian philosophical novel by Walker Percy. The writer of this page holds that High Fidelity, Garden State, The Graduate, The Truman Show, American Beauty, Harold and Maude, Adaptation and Sideways are similarly themed.

I quote from The Moviegoer:

“Today is my thirtieth birthday and I sit on the ocean wave in the schoolyard and wait for Kate and think of nothing. Now in the thirty-first year of my dark pilgrimage on this earth and knowing less than I ever knew before, having learned only to recognize merde when I see it, having inherited no more from my father than a good nose for merde, for every species of shit that flies – my only talent – smelling merde from every quarter, living in fact in the very century of merde, the great shithouse of scientific humanism where needs are satisfied, everyone becomes an anyone, a warm and creative person, and prospers like a dung beetle, and one hundred percent of people are humanists and ninety-eight percent believe in God, and men are dead, dead, dead; and the malaise has settled like a fall-out and what people really fear is not that the bomb will fall but that the bomb will not fall – on this my thirtieth birthday, I know nothing and there is nothing to do but fall prey to desire.”

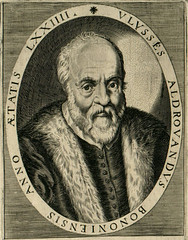

More info over at Kierkegaard and Arcimboldo.