Carl Theodor Dreyer, Danish film director (1889 – 1968)

Most iconic image of Dreyer’s career, from Vampyr

Second most iconic image of Dreyer’s career, from Vampyr

Still from The Passion of Joan of Arc

Still from The Passion of Joan of Arc

Carl Theodor Dreyer (February 3, 1889 – March 20, 1968) was a Danish film director. He is regarded as one of the greatest directors in cinema. Although his career spanned the 1910s through the 1960s, his meticulousness, dictatorial methods, idiosyncratic shooting style, and stubborn devotion to his art ensured that his output remained low. In spite of this, he is an icon in the world of art film.

At the same time he produced work which is of interest to film lovers with sensational inclinations, which merits his placement in the nobrow canon.

Thus, we tend to remember best of his oeuvre films such as Vampyr (a vampire film) and The Passion of Joan of Arc (for its execution by burning scene).

The Passion of Joan of Arc

The Passion of Joan of Arc is a silent film produced in France in 1928. It is based on the trial records of Joan of Arc. The film stars Renée Jeanne Falconetti and Antonin Artaud.

Though made in the late 1920s (and therefore without the assistance of computer graphics), includes a relatively graphic and realistic treatment of Jeanne‘s execution by burning. The film stars Antonin Artaud. The film was banned in Britain for its portrayal of crude English soldiers who mock and torment Joan in scenes that mirror biblical accounts of Christ’s mocking at the hands of Roman soldiers.

Scenes from Passion appear in Jean-Luc Godard‘s Vivre sa Vie (1962), in which the protagonist Nana sees the film at a cinema and identifies with Joan. In Henry & June Henry Miller is shown watching the last scenes of the film and in voice-over narrates a letter to Anaïs Nin comparing her to Joan and himself to the “mad monk” character played by Antonin Artaud.

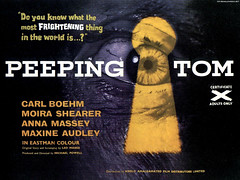

Vampyr

Vampyr is a French-German film released in 1932. An art film, it is short on dialogue and plot, and is admired today for its innovative use of light and shadow. Dreyer achieved some of these effects through using a fine gauze filter in front of the camera lens to make characters and objects appear hazy and indistinct, as though glimpsed in a dream.

The film, produced in 1930 but not released until 1932, was originally regarded as an artistic failure. It got shortened by distributors, who also added narration. This left Dreyer deeply depressed, and a decade passed before he able to direct another feature film, Day of Wrath.

Film critics have noted that the appearance of the vampire hunting professor in Roman Polanski‘s film The Fearless Vampire Killers (1967) is inspired by the Village doctor played in Vampyr. The plot is credited to J. Sheridan Le Fanu’s collection In a Glass Darkly, which includes the vampire novella Carmilla, although, as Timothy Sullivan has argued, its departures from the source are more striking than its similarities.

Vampyr shows the obvious influence of Symbolist imagery; parts of the film resemble tableau vivant re-creations of the early paintings of Edvard Munch.

Vampyr and The Passion of Joan of Arc are World Cinema Classics #83 and 84.