Pure War (1983/1998) – Paul Virilio, Sylvère Lotringer [Amazon.com] [FR] [DE] [UK] […]

Gravity’s Rainbow (1973) – Thomas Pynchon

[Amazon.com] [FR] [DE] [UK]

Note to self: check connection between Paul Virilio’s concept of pure war and the military-industrial complex to Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. Tip of the hat to Kris Melis.

For now: some Google connections of which the strongest is the one by Nick Spencer:

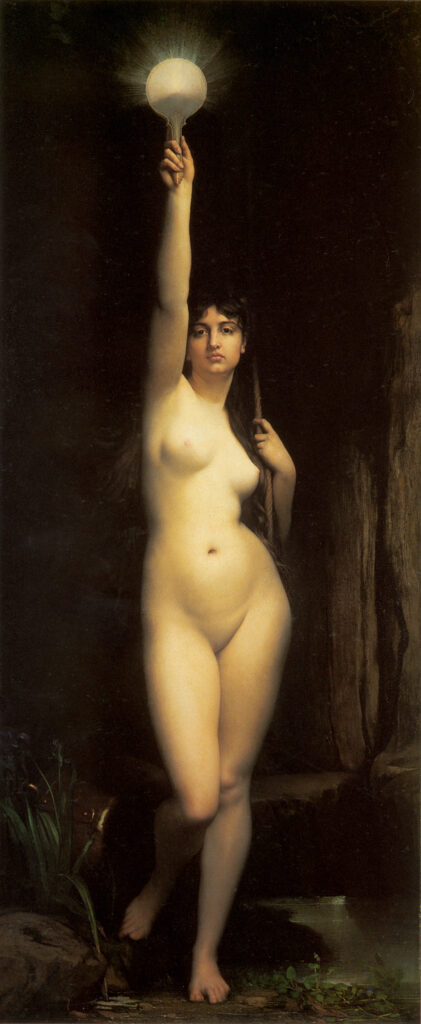

Despite multiple claims that the era of postmodernity represents a radical shift in the epistemology and ontology of western societies, many commentators stress the continuities between postmodernism and earlier historical periods. Such a project either takes the form of discerning postmodernism avant la lettre – say in the literary texts of Cervantes, Sterne, or Joyce, or the philosophies of the pre-Socratics – or of assessing traces and residues from the political, cultural, and philosophical past which remain within contemporary western culture. In this latter respect, the legacy of romanticism has been particularly strong. Even those elements which are apparently unique to postmodernism – the technologization of experience and the decentering of subjectivity, to name but two – are partly derivative of romanticist notions such as the mystification of electricity and scientific devices, and the awareness of unconscious forces which can overwhelm and fragment the subject. –Nick Spencer, Clausewitz and Pynchon: Post-Romantic War in Gravity’s Rainbow, via here.