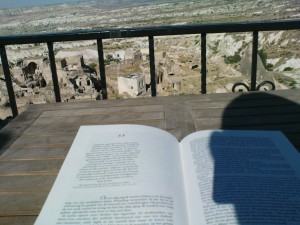

My copy of ‘Foucault’s Pendulum’ overlooking the Pigeon Valley from the rooftop of Has Konak in Cappadocia

As is often the case, the most salient bits of a book only become apparent a while after finishing it.

So it was only after a week or so after digesting the 600+ pages of Foucault’s Pendulum that the phrase “urban planning for gypsies” suddenly sounded in my ears:

‘Listen, Jacopo, I thought of a good one: Urban Planning for Gypsies.’

‘Great,’ Belbo said admiringly. ‘I have one, too: Aztec Equitation.’

‘Excellent. But would that go with Potio-section or the Anynata?’

‘We’ll have to see.’ Belbo said. He rummaged in his drawer and took out some sheets of paper. ‘Potio-section…’ He looked at me, saw my bewilderment. ‘Potio-section, as everybody knows, is the art of slicing soup. No, no,’ he said to Diotallevi. ‘It’s not a department, it’s a subject, like Mechanical Avunculogratulation or Pylocatabasis. They all fall under the heading of Tetrapyloctomy.’

‘What’s tetra…?’

‘The art of splitting a hair four ways. Mechanical Avunculogratulation, for example, is how to build machines for greeting uncles.’

As it turns out, “urban planning for gypsies, the art of slicing soup, Morse syntax, the history of antartic agriculture, the history of Easter Island painting, contemporary Sumerian literature, Montessori grading, Assyrian-Babylonian philately, the technology of the wheel in pre-Columbian empires, and the phonetics of the silent film” and other nonsensical endeavors are part of what Eco has termed the cacopedia.

What baffled me while reading Foucault’s Pendulum, is the commercial success of the novel, a book full of esoteric references to the Kabbalah, alchemy and conspiracy theories.

It makes you wonder what the owning/reading ratio is. Just imagine the number of people who bought it or got it as a gift but left it unopened on their shelves.

The book is unreadable for the uninitiated, the name-dropping is so extensive that critic and novelist Anthony Burgess suggested that it needed an index. In fact, Wikipedia produced two of them: Concordance of Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum and Concordance of Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum (2).