Yesterday evening on Arte TV (along with the BBC, one of the best television stations in Europe) there were two documentaries about the sexual revolution in Europe. The first documentary was on Lasse Braun and it was followed by a documentary on the sexual revolution as it happened in Denmark, what I have called the ‘Danish experiment’ before. I fell asleep during this second part, so some notes about the Braun feature:

Worth remembering about Lasse Braun (born 1936) is that he spent some time in Breda, The Netherlands, which was his most fruitful time; that he was/is somewhat of an intellectual/guru type of person (equalling pornography to anarchism (a practice which started in 18th century Europe)) and that he is a sexually dominant who works with women who were/are in love with him.

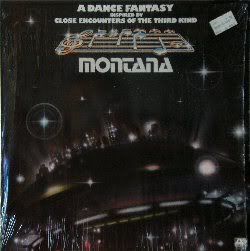

Sensations (1976) – Lasse Braun

There was an interesting interview with Tuppy Owens (Britain’s leading “pro-sex” (a radical group within the post-feminist camp) writer and activist, comparable to the likes of Annie Sprinkle, Susie Bright etc in America). Tuppy Owens appeared in the 1976 film Sensations, Braun’s first feature film and a good illustration of the shift of pre-1970s pornographic film (usually filmed on 8mm and 16mm formats and distributed in brothels and peep show booths) to porn chic films (filmed on professional stock and shown in ‘mainstream’ theatres.)

The end of the documentary saw Lasse Braun in Susan Block’s TV show, a very sad affair indeed.

See also: European pornography– sexual revolution in the cinema