A large part of my wiki is about tracing certain sensibilities around the globe. Recently, I made two discoveries which ‘opened’ Portugal and Belgium for me.

I found – what I believe to be – the Portuguese equivalent of Western publishing houses Losfeld, Pauvert, Olympia in France, März in Germany, Calders & Boyars in the UK or Grove Press in the U. S. : Edições Afrodite run by Fernando Ribeiro de Mello. Most of the info comes from the Portuguese Wikipedia and much of it still needs to be translated. My Portuguese is limited, so any help is welcome.

Quite a wonderful cover:

Textos Malditos, an Edições Afrodite edition

Rita Renoir, enz.

In Belgium I found Freddy de Vree, Belgian intellectual, cult figure and companion to Sylvia Kristel in the last years of his life. He was a friend of Topor and W. F. Hermans, wrote critiques on such diverse topics as Pigalle stripteaseuse Rita Renoir or French ‘excremental’ philosopher Georges Bataille.

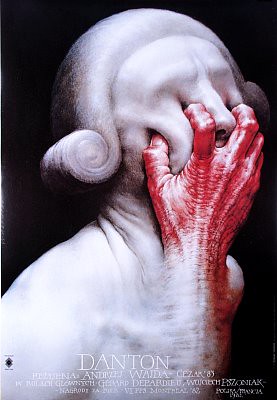

Below are two images from De Bezige Bij editions of Hermans’s King Kong by publisher De Bezige Bij, of which I found the graphics amazing. De Bezige Bij, an interesting Dutch publishing house.

Two very impressive Bezige Bij covers:

King Kong

King Kong tweede druk

De Bezige Bij also published De Vree’s book on W. F. Hermans: De aardigste man van de wereld.

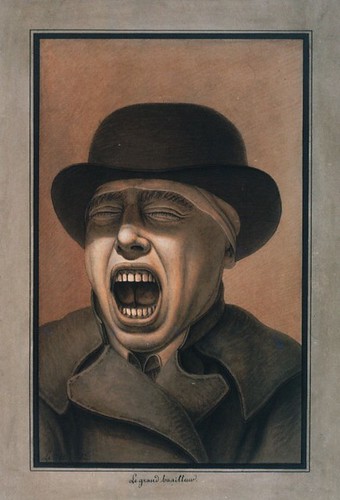

I thought it would be nice to leave you with an image of Rita Renoir: