In search of Custos and Liceti and the representation of monstrosities in general.

A “colonel of the Tartars (des Turqs) and a soldier”, captured in 1595, drawn by Domenicus Custos [1]

Dominicus Custos (1550/60–1612) was a copper engraver in Antwerpen and Augsburg.

Don’t forget to check the rest of [this page].

De Monstrorum (1616) – Fortunio Liceti

For the Italian physician Fortunio Liceti, true monstrosity inspired wonder and not horror. He criticized the association of monsters with divine wrath, and pointed out that the word ‘monster’ came from the Latin verb ‘monstrare,’ meaning ‘to show.’ Hence, Liceti argued, monsters were not signs of God’s punishment, but rather, they were creatures to be displayed because of their rarity. —source

In 1616 Liceti published De Monstruorum Natura which marked the beginning of studies into malformations of the embryo. He described various monsters, both real and imaginary, and looks for reasons to explain their appearance. His approach differed from the common European viewpoint of the time, as he regarded monsters not as a divine punishment but rather a fantastical rarety. He also supported the idea of transmission of characteristics from father to son. —Wikipedia

Elephant-headed man from Fortunio Liceti’s De Monstris (1665).

Amorphous Monster (Fortunius Licetus, De Monstris, 1665).

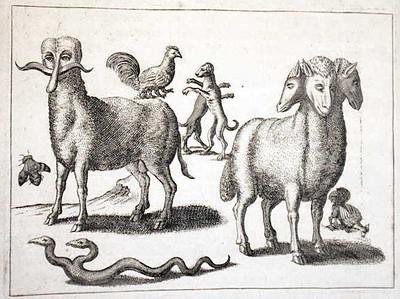

Pope-ass and other monsters from Fortunio Liceti’s De Monstrorum causis natura (1665).

These are some of the many oddities pictured in a treatise simply entitled De Monstris, by Fortunato (or Fortunio) Liceti (1577-1657), an Aristotelian scholar who also published works on hieroglyphics, spontaneous generation and astronomical controversies. —Il Giornale Nuovo

For those of you unfamiliar with this masterpiece of the genre:

Old Woman. (The Queen of Tunis)., Quentin Matsys, c. 1513. Oil on panel. National Gallery, London, UK