In early 2005, Fernando Botero revealed a series of 50 paintings (Google Gallery) that graphically represent the controversial Abu Ghraib incident, expressing the rage and shock that the incident provoked in the artist. The works were initially presented in Italy, Germany and Greece. In 2006, they had their first showing in the United States. In 2007, the Abu Ghraib series was exhibited at the University of California in Berkeley. Botero has stated that he does not plan to sell the paintings, but instead intends to donate them to museums as a reminder of the events depicted within. Are these on display somewhere now?

Monthly Archives: July 2007

RIP László Kovács

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6wtfNE4z6a8]

Five Easy Pieces, filmed by László Kovács (1933 – 2007)

Two recent brilliant films

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4pySXc-6GoU]

[Youtube=http://uk.youtube.com/watch?v=8GjjYHVj-mw]

From the director of Daft Punk’s ‘Around the World’ : The Science of Sleep

World cinema classics

[Youtube=http://youtube.com/watch?v=5AYnORotfq8]

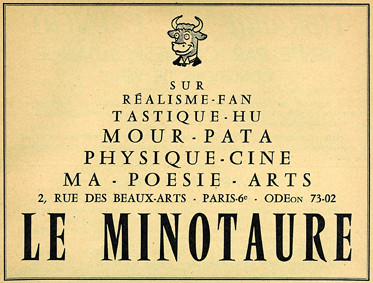

Le Minotaure

Le Minotaure was a Parisian bookstore founded by Roger Cornaille, located at number 2, rue des Beaux-Arts.

A tear of petrol is in your eye

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pWL4C7JbOw8]

“Warm Leatherette” is a 1978 single by The Normal, based on J. G. Ballard’s novel Crash.

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_p7Ub1NDTVg]

Another Daniel Miller project: Silicon Teens – Memphis Tennessee

Inspiration: Music to read Crash by

Italian underground #1

Cover of Cannibale, issue 3

image sourced here.

Cannibale was an Italian underground comics magazine with humoristic and satirical overtones. Founded by Stefano Tamburini and Massimo Mattioli in the winter of 1977 and last published in July 1979. They were the first to publish Tanino Liberatore‘s RanXerox, who was later translated all over the world. The best known authors were Stefano Tamburini, Filippo Scozzari, Andrea Pazienza, Tanino Liberatore, Massimo Mattioli.

Liberatore was 25 when he started to publish his first episodes of Ranxerox in Cannibale. Here he is in a 2002 interview with Tanino by vakiltd for Greek national television. Italian text and Greek subtitles.

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=13Aq5rog7Nk]

Sci-fi noir, or, on the longevity of generic categories

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zx8ohP7qro4]

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4lW0F1sccqk]

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3i3jT95NExE]

Sci-Fi noir is a term coined in the 2000s to denote a category of science-fiction films. Milestone films generally cited in this category are Jean-Luc Godard’s Alphaville (1965), Ridley Scott‘s Blade Runner (1982) and Ghost in the Shell (1995). As an aesthetic category, it is very near to cyberpunk and neo-noir. The work of Tanino Liberatore‘s RanXerox deserves mention here. One wonders how long this freshly-coined neologism will survive.

This collection of Youtube vids inspired by The Rise of Sci-Fi Noir by Broken Projector.

Burundi beat, or, obtaining copyright for a rhythm is a difficult proposition

Musique du Burundi (1968)

Burundi beat is best known as an appropriated drum style of British New Romantics bands Bow Wow Wow and Adam and the Ants.

The original source of this tribal rhythm is a recording of 25 drummers of the Ingoma tribe, made in 1967 in a village in Burundi by Michel Vuylsteke and Charles Duvelle, a team of French anthropologists. The recording was included on an album, Musique du Burundi, issued by the French Ocora label in 1968. (pictured above)

In 1971 Mike Steiphenson grafted an arrangement for guitars and keyboards onto the Ocora recording for Barclay Records, and the result was Burundi Black, a seven inch that sold more than 125,000 copies and made the British best-seller charts. In 1978, Barclay released a twelve inch version.

In 1981, the track was re-released on Barclay and Cachalot records. This time, Rusty Egan, drummer with the new romantic band Visage, and a French record producer named Jean-Philippe Iliesco recorded a new pop arrangement over the Burundian drummers.

Mike Steiphenson holds the Burundi Black copyright. Adam and the Ants, Bow Wow Wow, and several other bands have made hits with the Burundi beat as a rhythmic foundation. The Burundian drummers who made the original recording are not sharing in the profits. In any case, as the Jamaican recording industry and the Amen break cases have shown, obtaining copyright for a rhythm is a difficult proposition.

Momus on paratextual pleasures

Momus

“As a student of literature, something you find yourself doing a lot is reading books about books — narratives which tear through the plot outlines, critical receptions and choicest quotes of other books, giving you some kind of rapid gist or taste of hundreds of titles you’ll probably never read. What I’ve always liked about these books-about-books.”

He mentions

He also mentions the fact that the paratext is often better than the text itself

- “In a weird, inverted way, some of the books which must be most hellish to read in real life, in real time, turn out, in these metabook accounts, to be the most entertaining to read about” (see paratext).

Example of the latter:

This post reminds me of the following quote of O. Wilde:

- “I never read a book I must review, it prejudices you so.” —Oscar Wilde

and my own recent research in thematic literary criticism and my earlier praise of secondary literature.

Via the comments to Momus’s post we come to reviews of books we’ve never read. Stanislaw Lem wrote a few sets of introductions to and reviews of fictional books here and Borges has An Examination of the Work of Herbert Quain

To top it off there is ‘How to Talk of Books We Haven’t Read?‘ by Pierre Bayard.

Inspired by The dream life of metabooks