In search of intentional and unintentional similarities in fiction

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CrV1sfJHLHg]

Addio Zio Tom (Goodbye, Uncle Tom) (1971) by Gualtiero Jacopetti and Franco Prosperi

- “All events, characters and institutions in this motion picture are historically documented and any similarity to any person, black or white, or to any actual events, or institutions is intentional and anything but coincidential.” –from the credits to Goodbye Uncle Tom, see fictionalization and fiction disclaimer.

Thus opens or closes Goodbye Uncle Tom of which a clip is listed above and it provides an excellent introduction to the tenuous relation between fiction and reality.

Addio zio Tom (1971) – Gualtiero Jacopetti, Franco Prosperi

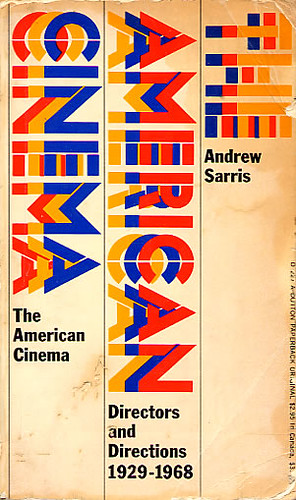

Image sourced here. [Dec 2005]

Two more quotes provide further food for thought:

- “It’s no wonder that truth is stranger than fiction.” Fiction has to make sense – Mark Twain

- “The mind of man can imagine nothing which has not really existed.” —Edgar Allan Poe, 1840

If we represent the relationship between fiction and reality on a sliding scale we find on the left hand side: fiction which makes no claim to reality. This kind of fiction is nowadays always preceded by the fiction disclaimer:

- “Any resemblance to persons living or dead is purely coincidental.”

The above is sometimes preceded by “The characters in this film are fictitious,”.

This kind of fiction is helped by Poe’s quote in its theoretical approach. If done well, this kind of fiction is called the fantastique, that area of literary theory which provides us with an unresolved hesitation as to our position on the reality/fictitiousness scale. Another growth of this kind of fiction is the roman à clef a novel and by extension any sort of fiction describing real-life events behind a façade of fiction. The reasons an author might choose the roman à clef format include satire and the opportunity to write about controversial topics and/or reporting inside information on scandals without giving rise to charges of libel.

On the right hand side of the scale we find fiction that does make claim to reality. This kind of fiction is nowadays usually preceded by the claim based on true events:

This kind of fiction is helped by Twain’s quote in its theoretical approach. Real stories are often so unbelievable that we need to make the claim that they are based on actual events.

As a narrator of fiction, one is always aided by this claim to capture the audience’s interest. This is true in the case of a joke (tell it as if it has happened to you), in the case of novels (Robinson Crusoe was soi-disant based on actual events) and film (Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) was supposedly about Ed Gein)

A whole range of concepts falls into this category, listed under the heading fictionalization: faction, based on a true story, false document, nonfiction novel, true crime (genre), histories (history of the novel), stranger than fiction and mockumentary.

The funny thing about the right hand position on the fiction/reality scale is that the act of narrating alters reality by default. I always illustrate this point by going back to your youth. You had a brother or sister and you fought with him over something. You went to your mother or father or any other judge-figure, who gave you both the opportunity to tell the story. You both came up of course with a different version.

Which brings me to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the observer effect. If the act of perception alters reality, the act of telling a story alters reality. That is why I dislike films such as Schindler’s List because in this case, “real” documentary material is available. Maybe this is also the case for Goodbye Uncle Tom, but boy, I sure would like to see that film.