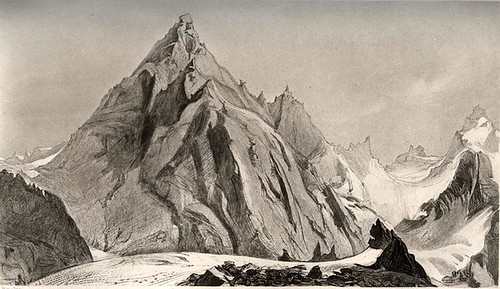

The Aigiulle Blaitiere. c. 1856 by John Ruskin

A painting by Thomas Hill dated 1870

Reading the opening chapter of Ivins‘s Prints and Visual Communication[1] on the indescribability of things (and the need for photographic representations) reminded me of the garland and the Greek Anthology.

Googling for “indescribability” brings up this interview regarding the sublime, indescribability and mountain literature and mountain art.

- The trope of unrepresentability is probably the commonest of all in mountain literature and art: the throwing up of the hands, the confession of the inadequacy of representation to catch the phenomena of the mountain world. I remember reading the journal of an Edinburgh bishop from the 1760s who’d gone on a mini-Caledonian tour. He writes: “I looked north and saw rank on rank of unspeakably beautiful…” He crosses out “unspeakably”—he’s obviously unhappy with it—and writes instead “mountains so beautiful I could not describe them.” Then he crosses that out, and we get four synonyms for “indescribable,” the first three crossed out. What’s exciting about Ruskin is that instead of acquiescing to indescribability, he tries to enact it, to let his art or prose take the forms of their subjects. In his drawing of the Glacier du Bois, near Chamonix, for example, the whole image is vortical; everything is being tugged by some centripetal force which has no apparent center but which is clearly at work. It’s hard to say what that force is, but it has something to do with time, a kind of deep time that is at work in that viewing moment. The glacier looks like a river in flood, in spate; the sun looks to have been absorbed by it, and there’s an inexplicably detached tree bole and root in the foreground. Even his curving signature seems to be vulnerable to the vortex. –Brian Dillon interviewing Macfarlane [2]

My love for subjects starting with un-, in-, a- and variants is great and started with with the notion of unfilmability. Notable related concepts to indescribability include unspeakable, ineffable and inexplicable.

They connote to absence, lacking, contrary, opposite, negation and reversal, concepts and tropes very apt to denote their positive counterparts.

For what is there to say on effability if one does not investigate its negative: ineffability?

The whole of this subject touches on representation in the arts and of course, medium specificity.

Older links to this subjects are general aesthetics and the sublime.

To end with a quote which I cannot reproduce verbatim:

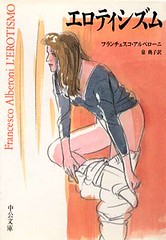

- “Sex begins where words stop”. —Georges Bataille.

I’ve explored the previous notion here[3].