Via Bright Stupid Confetti[1] comes Christophe Bruno‘s Dadameter

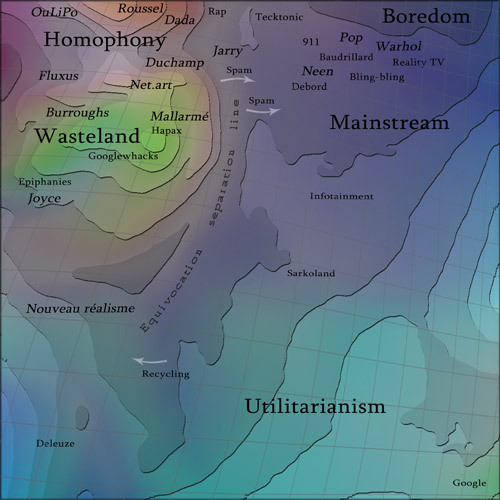

The Dadamap

Christophe Bruno (born July 1, 1964) is a French artist. He began his artistic activity in 2001, influenced by the net.art movement. His thesis is that through the web, and especially through the ability to search and monitor it thoroughly by means of Google, we are heading towards a global text that among other things enables a new form of textual, semantic capitalism, which he explores in his work. His artworks include Iterature, Logo.Hallucination, The Google Adwords Happening and many other pieces.

The Dadameter is an art project by French artist Christophe Bruno first presented in 2008. It was inspired by the work of french writer Raymond Roussel use of homophony described in How I Wrote Certain of My Books.

In the words of the Bruno “the project is a satire about the recent transmutation of language into a global market ruled by Google et al. and uses the most up-to-date technologies of control to draw cartographies of language at large scale.”

It was co-produced by the Rencontres Paris-Berlin-Madrid 2008 for contemporary art and new cinema and programmed by Valeriu Lacatusu.

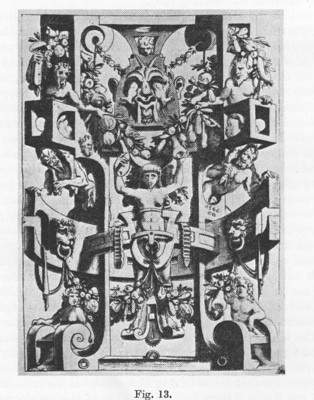

The result of the project is the so-called Dadamap[2][3] in which each pixel corresponds to one couple of words. The project started from “a lexicon of several thousands of words which correspond to about 800,000 couples (as many pixels then), and we looked for homophonic correlations, as in billard / pillard [see Roussel], or for semantic correlations.”

The procedure provides three measurements for each couple of words corresponding to homophony (the Damerau-Levenshtein distance), Google Similarity (or semantic relatedness) and thirdly equivocation (to which extent a word has a univocal meaning or at the contrary is polysemic or equivocal).

The Dadamap is a topographical map resembling an ocean floor, it features green for wasteland, light blue for utilitarianism, blue for mainstream, deep blue for boredom and brown for homophony[4]. There is an equivocation separation line which roughly splits the map into two, or maybe that is a rift. From left to right, the map contains the following lemmata: OuLiPo, Roussel, Dada, rap, Tecktonik, 911, pop, Warhol, Fluxus, Duchamp, Jarry, Baudrillard, reality TV, spam, neen, bling-bling, net.art, Debord, Burroughs, Mallarmé, spam, Hapax, Googlewhacks, epiphanies, infotainment, Joyce, Nouveau Réalisme, Sarkoland, recycling, Deleuze and Google.