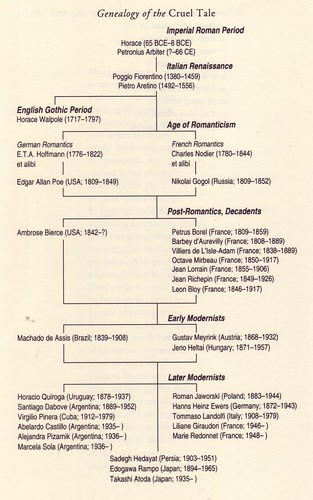

Charles Nodier‘s Infernaliana

Most of the afternoon has been spent on literary lunatics and morosophy, inspired by researching Charles Nodier‘s Infernaliana[2], brought to my attention by Au carrefour étrange[3]. One encounters[4] the recently discovered but already inevitable JRMS[5] on the way. Do listen to the latter’s current Studio One muxtape[6].

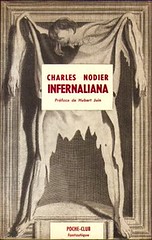

I’m kind of happy that I managed to dug out the special issue Hétéroclites et fous littéraires[7][8] from Bizarre at L’Alamblog and particularly satisfied with my translation of the French-language Wikipedia article on “literary lunatics“:

Fous littéraires is a French term used to denote outsider writers who have failed to attract any recognition, not by the intellegentiae, not by the public, not by art critics, not by publishers (since they are largely self-published), and which treat subject matter considered – at least by those who qualify these writers as fous littéraires – as offbeat and amusing, without this being the intention of the author. A prime example in this category is Jean-Pierre Brisset, French author of Les dents, la bouche, a poem which is untranslatable due to its reliance on paronymy.

The study of literary fools starts in 1835 with a bibliography compiled by Charles Nodier (Bibliographie des fous : De quelques livres excentriques, published by Techener in 1835) and is continued in 1880 with Gustave Brunet (aka Philomneste Junior) in Les Fous littéraires, essai bibliographique sur la littérature excentrique, les illuminés, visionnaires, etc., published by Gay et Doucé in 1880.

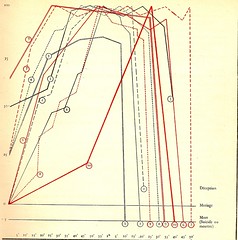

In the 1930s, Raymond Queneau continues the projet by spending years of research at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, fruits of which include Les Enfants du limon[9] (1938) and the posthumously published Aux Confins des Ténèbres, les fous littéraires.

Official Oulipo photo, André Blavier in cardboard cutout on table

In 1982 Henri Veyrier published Les Fous littéraires, a work of Belgian surrealist André Blavier[10], a continuation of his predecessors (and work he had published in Hétéroclites et fous littéraires in Bizarre of April 1956) with an augmentation by Malombra/Roger Langlais estate. This veritable encyclopedia features more than 1000 pages and 3000 reviewed “auteur“s. It features inventors of perpetual motion, theorists who claim the answer to squaring the circle, the inexistence of hell, universal languages, the structure of the universe, medicine, algebra or human sexuality.

In 2007, a group of French-language writers, found the IIREFL (Institut international de recherches et d’explorations sur les fous littéraires, hétéroclites, excentriques, irréguliers, outsiders, tapés, assimilés, sans oublier tous les autres…) or in English: International Institute for Research on Literary Lunatics, Outsiders, Weirdoes, Assimilated, say nothing of the others….

Proving that I do venture outside at times:

after Sherrie Levine, after Edward Weston

Taking photos of photos seems to be my thing. With my new camera, after Sherrie Levine, after Edward Weston, I took a picture of this polaroid[11] by Guy Bourdin (Bourdin used the pola in [12]) yesterday night (which was museum night) at the Antwerp fotomuseum. There are some more of my snapshots of Bourdin’s polaroids[13].

2008 art intervention at MuHKA

My friend and I also had our picture taken[14] at the Guillaume Bijl installation TV Quiz Decor[15]. We were chased away by a museum attendant, but I managed to soothe her saying it was an art intervention.