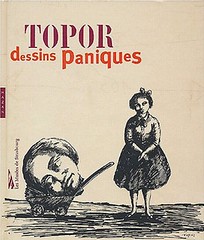

What follows are some notes on Baj with pointers to some interesting paintings. I can’t remember when and where I first discovered Baj. Perhaps through Virilio, or by way of Topor or Joe Colombo?

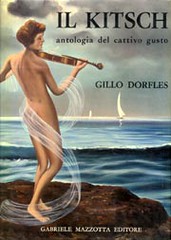

Kitsch (1968) – Gillo Dorfles

Enrico Baj (October 31, 1924 – June 16 2003) was an Italian avant-garde artist and art writer. Baj’s work shows similarities with Jean Dubuffet, Roland Topor and the COBRA group. It has a grotesque quality. Baj has also collaborated with Paul Virilio in a book on art horror, Discourse on the horror of art.

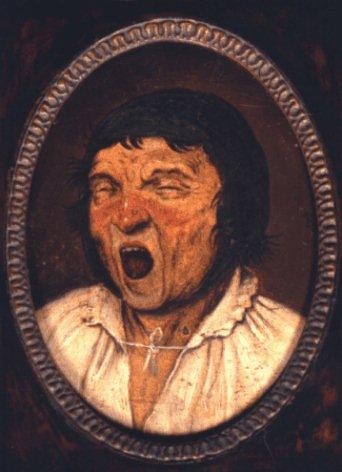

The book on Enrico Baj I bought today is an edition by Ronny van de Velde. Its title is Modifications. It is the catalog of an exhibition which was held in Antwerp in 1998. (détrompe l’oeils or modifications by Daniel Spoerri, Enrico Baj and Asger Jorn). It brings to the fore a to me unknown fascination of Baj with kitsch in his paintings from the 1959-1964 period. One of the paintings shown, the 1968 “Miss Paganini Non Ripete” depicts UFO’s superimposed on the same painting that Gillo Dorfles used on the cover of his 1968 book Kitsch, an anthology of bad taste (shown above). Many paintings in Modifications have this same working method, works of bad taste “detourned” by Baj.

- Four untitled modifications with Daniel Spoerri and Enrico Baj (1955-1957?): 1, 2, 3, and 4 via Not Bored.

- Adam and Eve by Baj