One could easily be tempted to attribute common etymological roots to the words caricature and character. In fact their etymologies are not connected but that does not stop us from associating the two concepts.

Yesterday, I stumbled upon an epigraph by Poe: “Ce grand malheur, de ne pouvoir être seul,” which translates to Such a great misfortune, not to be able to be alone. It is from Poe’s short story “The Man of the Crowd,” but Poe had quoted it before, in his earliest tale, “Metzengerstein.”

Poe attributes it to Jean de La Bruyère, who wrote the Caractères (Eng: The Characters of Jean de La Bruyère). Bruyère’s book is an “augmented” translation of Theophrastus‘s (371 – c. 287 BC) The Characters which contains thirty brief, vigorous and trenchant outlines of moral types, which form a valuable picture of the life of his time, and in fact of human nature in general.

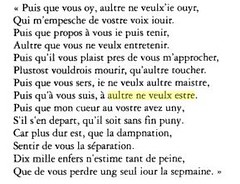

The genre of the “character sketch” is generally cited as originating in Theophrastus’s typology. One of the thirty sketches of Theophrastus reads thus:

Of Obscenity, or Ribaldry “Impurity or beastliness is not hard to be defined. It is a licentious lewd jest. He is impure or flagitious, who meeting with modest women, sheweth that which taketh his name of shame or secrecy. Being at a Play in the Theatre, when all are attentively silent, he in a cross conceit applauds, or claps his hands: and when the Spectators are exceedingly pleased, he hisseth: and when all the company is very attentive in hearing and beholding, he lying alone belcheth or breaketh wind, as if Æolus were bustling in his Cave; forcing the Spectators to look another way …”, translation by Joseph Healey

More recent writing inspired by Theophrastus includes George Eliot‘s 1879 book of character sketches, Impressions of Theophrastus Such.

What I particularly like about these character sketches are their plotlessness, their roots as inspiration for the psychological novel, there generalizations into stereotypes and stock characters, and finally, their link to caricatures and physiognomy.

This post was illustrated by Characters Caricaturas (1743) by William Hogarth.