As you may have heard, I have resumed my work as pornosopher and I am currently writing my master’s thesis which investigates whether porn can be art. In my research I get lost very often (which kind of seems to be the purpose).

However, it is time for me to stop getting lost, because I have another paper to finish on political myth, a paper which I have tentatively titled “Mythe, meute, Europa,” which translates as “Myth, mob, Europe.”

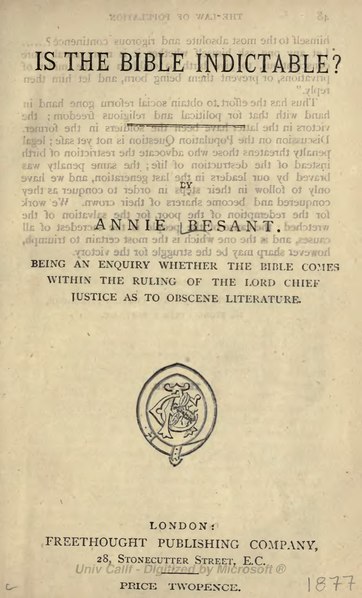

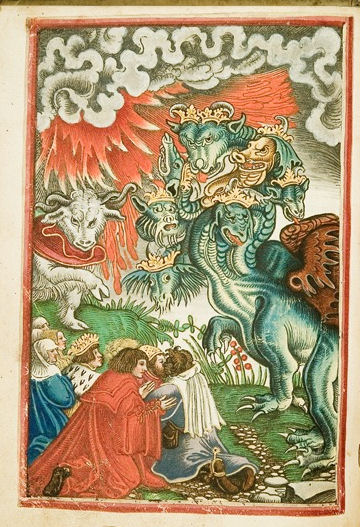

Before I start that work, one of my most satisfying finds of the latest obsessive quest: Annie Besant’s sublime pamphlet: “Is the Bible Indictable?” (illustration).

Besant asks (in 1877, mind you!):

“Does the Bible come within the ruling of the Lord Chief Justice as to obscene literature? Most decidedly it does, and if prosecuted as an obscene book, it must necessarily be condemned, if the law is justly administered.”