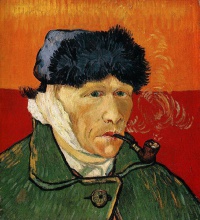

Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe by Eugène Bataille (Sapeck) (page from the book Le rire, source Gallica.bnf.fr)

I’ve been fascinated by the Incoherents since I first stumbled upon them in 2007[1][2].

After becoming a member of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp library some weeks ago, I have been able to consult two seminal books on that movement’s history: the Arts incoherents, academie du derisoire exhibition catalog (1992) by Luce Abélès/Catherine Charpin and The Spirit of Montmartre: Cabarets, Humor and the Avant-Garde, 1875-1905 (1996) by Phillip Dennis Cate.

Object of my research was to check the dates of works I consider canonical to the proto-avant-garde, dates which I previous held to be the neat series of 1882, 1883 and 1884.

It’s a pity, but I’ve had to adjust that series to 1882, 1883 and 1887: Negroes Fighting in a Tunnel at Night (1882), Funeral March for the Obsequies of a Deaf Man (1884) and Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe (1887).

According to my research, Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe by Sapeck, which is still listed over at Wikipedia as originating in 1883 and erroneously titled as Le rire, in fact first saw the light of day in 1887, in the book Le Rire by Coquelin cadet.

Wikipedia is not the only reference work in error. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines erroneously states that this Mona Lisa was first shown in 1883 at the second “Incohérents” exhibition.

What is the importance of this augmented Mona Lisa?

Simple.

Perhaps the invention of high art with capital ‘A’ coincided with the first blows of its ridicule. This augmented Mona Lisa was a desecration, a violation, a rape of its masterpiece: the Mona Lisa proper by da Vinci.

Think about it.

.jpg)