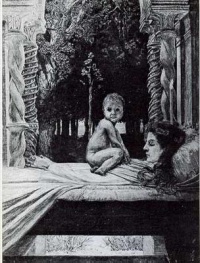

No-Stop City, Interior Landscape, 1969 by Archizoom Associati

It was American experimental musician Rhys Chatham who first pointed out that the energy of art is always equal (except in periods of extreme hardship such as famine and war, where production tapers off), but has at the same time the tendency to displace itself. In music for example, the energy in the 1950s was in rock and roll, in the 1980s it was to be found in house music and techno.

The energy in international design in the late 1960s and early 1970s was clearly to be found in Italy. Displayed above is No-Stop City, a “radical design” architectural project by Archizoom Associati first introduced to the public in 1969. It is a critique of the ideology of architectural modernism, of which Archizoom felt that it had reached its limits. The artistic discourse of that era was buzzing with the term neo avant-garde, in a period that corresponds with Late Modernism or early postmodern art. The term neo avant-garde was rejected by many, but the term can be interpreted to refer to a second wave of avant-garde art such as Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, Nouveau Réalisme and Fluxus.

If you want to read up on this period, please consult the following excellent volume:

The Hot House (1984) – Andrea Branzi [Amazon.com] [FR] [DE] [UK]

Prices in Amazon Europe are around 40€, in America starting from 12USD, a bargain.