Women read fiction, men read non-fiction[1], I wrote in 2006 and the subject has continued to intrigue me from three perspectives.

- Just what is the nature of the reading experience in pre-cinematic and cinematic eras?

- Women have always read more fiction, women have often been the first professional writers and have produced a score of successful authors (most recently I found the example of Neel Doff in the Néerlandosphere), yet have been patriarchally excluded from literary histories.

- Reading too much is undesirable, it will give you too much knowledge, too much knowledge kills (cfr. tree of knowledge, curiosity killed the cat, The Man Who Knew Too Much, The Girl Who Knew Too Much, but also see Anna Karenina and Emma Bovary and the danger of reading too much.

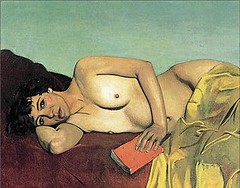

So what about the depiction of literature in painting? How about visual depictions of women reading? What about the female reader, the lectrice?.

Lady Reading the Letters of Heloise and Abelard (c.1780) is an oil painting measuring 81 x 65 cm .

It was painted by French painter Auguste Bernard d’Agesci and its subject was a female reader swooning over the star-crossed correspondence by Abelard and Heloise in the posthumously published Letters of Heloise and Abelard. The Letters of Heloise and Abelard are a series of letters between French priest Peter Abelard and his female student Héloïse after their separation and his castration.

Love letters, it must be said, has been one of the most popular genres in the history of literature. Consider the aforementioned Letters of Heloise and Abelard, but also Letters of a Portuguese Nun and Love-Letters Between a Nobleman and His Sister. See also amatory fiction and the epistolary novel.

“Love letters, it must be said, has been one of the most popular genres in the history of literature.” Why? Because it reduces the reader to the part of eavesdropper or voyeur, it allows you to step out of yourself and live the life of another.

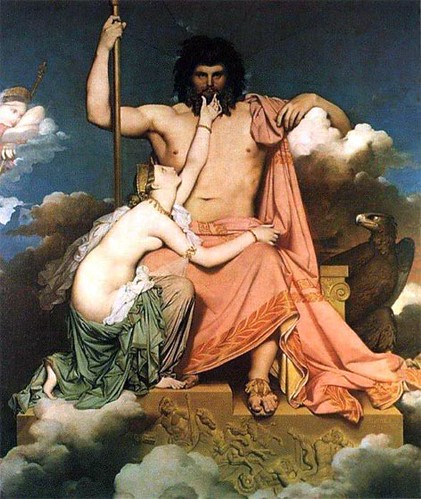

The passage you all want to read: the castration episode

- “[Fulbert] bribed my servants; an assassin came into my bedchamber by night, with a razor in his hand, and found me in a deep sleep. I suffered the most shameful punishment that the revenge of an enemy could invent; in short, without losing my life, I lost my manhood. So cruel an action escaped not justice, the villain suffered the same mutilation, poor comfort for so irretrievable an evil. I confess to you that shame more than any sincere penitence made me resolve to hide myself from the sight of men, yet could I not separate myself from my Heloise.” in a translation/edition by John Hughes, Pierre Bayle