Paul Rumsey is a British artist working in the tradition of the fantastique.

Category Archives: transgression

The beneficial side-effects of censorship

Cover of the 1937 guide book to the Degenerate Art Exhibition.

Nazi Germany disapproved of contemporary German art movements such as Expressionism and Dada and on July 19, 1937 it opened the travelling exhibition in the Haus der Kunst in Munich, consisting of modernist artworks chaotically hung and accompanied by text labels deriding the art, to inflame public opinion against modernity and Judaism. The cover the 1937 guide book (illustration top) features a sculpture of unknown origin. It could be Polynesian or any other tribal art work, please help me out here.

The sculpture clearly links modern art with primitivism.

This exhibition is also a perfect illustration of the beneficial side-effects of censorship. Beneficial in the sense that any attempt at banning works of art, books or other cultural artifacts results in an aide to discerning culturati to seek out these artifacts with zeal. Such has been the case with Video Nasties, the Index Librorum Prohibitorum (the Catholic Index) and the Degenerate Art expo mentioned above.

I once again repeat my question to you, dear reader: what is the origin of the statue depicted in the picture above. I thank you beforehand for a reply.

Icons of erotic art #16

Frontispiece by Fernand Khnopff for Joséphin Péladan’s Istar (1888)

Istar is a novel by Joséphin Péladan first published in 1888 with a frontispiece by Fernand Khnopff, depicting a woman, head thrown back in ecstasy and completely devoid of surrounding except for a phallic tentacled plant that grows toward her pubic area.

Eroticism 4/5, because of its “his hands were all over me” thematics first celebrated in icons #12 and 13.

Previous entries in Icons of Erotic Art here, and in a Wiki format here.

Eye candy #6

I had been intrigued by this cover of French decadent author Rachilde’s Monsieur Vénus for a while, and I always wondered what the cover was, even asking the blog Morbid Anatomy, which specializes in this kind of material, what it was.

It turns out that this is the origin of the photograph. The anatomical sculpture was produced by André Pierre Pinson (1746-1828), a French ‘medical artist’, who made the sculpture called La Femme assise (the seated woman). Voila. Case closed.

Previously on Eye Candy.

World cinema classics #34

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LwaPJUtZBYc&]

Tokyo Decadence (1992) – Ryu Murakami

This is a film I chose in the mid 1990s at the video store because of its cover, not being familiar at the time with the work of Murakami (Coin Locker Babies). The key scenes are four sex scenes (see more at the wiki). Three out of these heavily feature drugs. The most exquisite one, featured in the Youtube remix above, is soundtracked by Xavier Cugat music. The audio used in this particular Youtube remix is not included in the original film. I wonder what the music is. Anyone? (De temps en temps is a song (André Hornez / Paul Misraki) voiced by Josephine Baker.)

The film’s only rival in terms of my favourite film of the 1990s is the Japanese film Audition, which is also written by Murakami.

Previous “World Cinema Classics” and in the Wiki format here.

Satisfied that the photograph has been censored

Death by a Thousand Cuts is certainly one of the most gruesome photographs in the history of visual culture. I first encountered the photo online and later when I purchased Georges Bataille’s The Tears of Eros (currently available from City Lights). The version above is from the Dutch booklet Kaarten (1967, published by Born N.V.) an excellent little study by Drs. P on his postcards with a full bibligraphy on contemporary books on collecting postcards which even mentions Ado Kyrou’s treaty of the subject, L’age d’or de la carte postale (1966) which I have in my collection.

What is particular of this postcard is its obvious censorship. And actually, for once I’m really satisfied that the photograph has been censored, because I would not like to show it to you in its original version. The notes to the postcard read “Ling-chi” or “One thousand cuts”, the barbarous death penalty for a parricide in China. Published by Karl Lewis, no. 102, Honmura Road, Yokohama, Japan.

Blazon of the Ugly Tit

Contreblason du Tetin (1535) (Eng: Blazon of the Ugly Tit) is a poem by Clément Marot on ugly female breasts. Here in a translation by Helene Marmoux [1]. Clément Marot (1496–1544), was a French poet of the Renaissance period, for his poems on body parts, known as blasons and contreblasons. The ugly woman is a surprisingly common figure in Renaissance poetry, one that has been frequently appropriated by male poetic imagination to depict moral, aesthetic, social, and racial boundaries. The subject has been treated in dept by Patrizia Bettella in The Ugly Woman: Transgressive Aesthetic Models in Italian Poetry from the Middle Ages to the Baroque ( 2005).

Tit, skinny tit,

flat tit that looks like a flag,

big tit, long tit,

tit, must I call thee bag?

Tit with its ugly black end,

forever moving tit.

Who would boast having touched you?

With their hand fondle you? more…

Tip of the hat to On Ugliness

Eye candy #4

Surprising about the book, is that it is as much about literature than about visual culture. A big disappointment is that two times Eco says that “decency forbids us to reproduce such and such excerpt,” a childish remark. New authors and works discovered so far is Teofilo Folengo‘s Baldus (1517), of who Eco says that it was an important source of inspiration for Rabelais and Hieronymus Bosch.

In the beginning of the book, Eco makes a feeble attempt to come to a three-fold aesthetics of the ugly, but he never returns to his framework.

Actually, his thematics are not really the ugly, but the aestheticization of the ugly, a concept we know better as the grotesque, and which has been treated by such authors as Wolfgang Kayser in his The Grotesque in Art and Literature (which I have yet to read).

For those of you unfamiliar with the work of Salvator Rosa:

Salvator Rosa (1615 – March 15, 1673) was an Italian painter, poet and printmaker best known as an “unorthodox and extravagant” and a “perpetual rebel” proto-Romantic. His life and writings were equally colorful. Some sources claim he spent time living with roving bandits. Ann Radcliffe was greatly influenced by the Italian landscape painter and his dramatic landscapes peopled with peasants and banditti. Radcliffe managed to translate Rosa’s visual feeling of awe and the sublime to the Gothic novel popular in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Rosa is canonical to me despite of Huxley’s negative criticism:

- “Another more celebrated fantasist was Salvator Rosa — a man who, for reasons which are now entirely incomprehensible, was regarded by the critics of four and five generations ago as a great artist. But Salvator Rosa’s romanticism is pretty cheap and obvious. He is a melodramatist who never penetrates below the surface. If he were alive today, he would be known most probably as the indefatigable author of one of the more bloodthirsty and adventurous comic strips.” —Aldous Huxley, Prisons (1949)

Previously on Eye Candy.

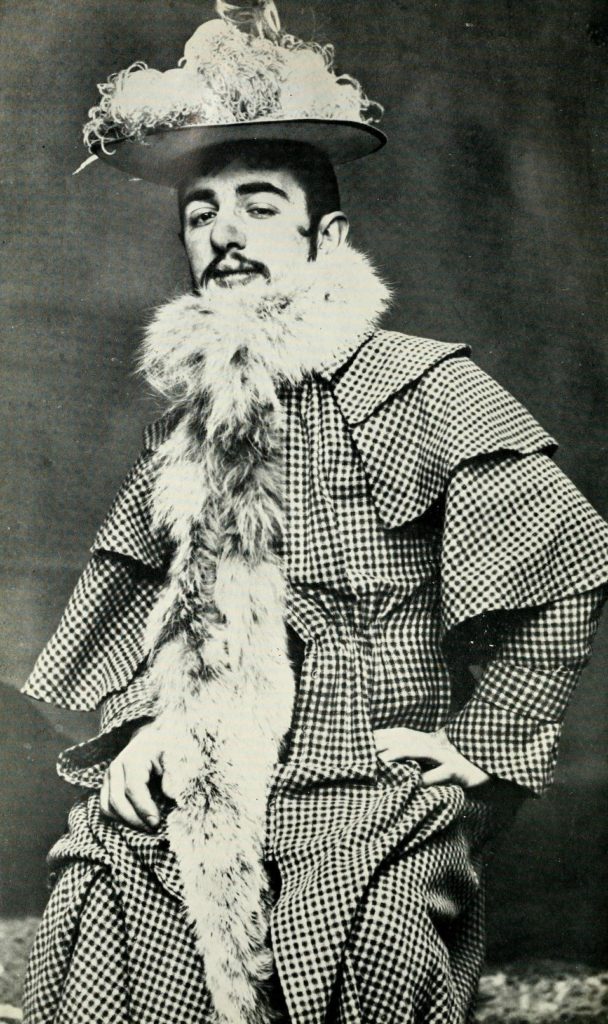

Toulouse-Lautrec in drag

in the clothes of Jane Avril,

a Moulin Rouge showgirl,

a photo by Nadar.

My best wishes for 2008, if you are a man, dress up as a girl and have a party. If you are a woman, help your man with his make up.

Related is this better-known photo of Marcel Duchamp in drag as Rrose Sélavy.

Look who’s back after a 6 month period of désœuvrement, French for idleness.

Icons of erotic art #10

As we have learnt from the first nine issues in this series, in the nebulous realm of erotic art, uneroticism runs rampant. Not with the photos I am about to present. NSFW, previously unpublished online, here is Unica Zürn photographed by Hans Bellmer [1].

Previous entries in Icons of Erotic Art here, and in a Wiki format here.