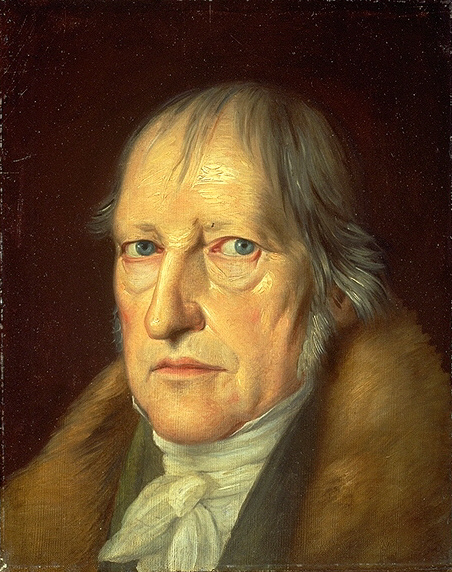

Portrait of Hegel by Jakob Schlesinger [1]

Sometimes it seems I have no opinion of my own. And I’m not even sure if I should mind.

Take the case of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770 – 1831).

Last week I met with a philosophy professor who said that Hegel marks the dividing line between contemporary philosophy and modern philosophy and in the book I’m currently reading, Short History of the Shadow, Hegel’s Science of Logic is mentioned in the introduction.

So I’m wondering. What is my position vis-à-vis Hegel? Do I have a personal connection with him? I first check Jahsonic.com where, in 2006, I cited Hegel[2] with regards to the other, from a Simone de Beauvoir book.

Speaking of de Beauvoir, have you seen her gorgeous nude photo of Simone de Beauvoir?

I digress.

Next I try Google, I search for the string “Nietzsche and Hegel,”[3] because Nietzsche (1844 – 1900) is in my canon and I’d like to know what he thought of Hegel.

I find French philosopher Gilles Deleuze, also in my canon, who in Nietzsche and Philosophy says:

- “There is no possible compromise between Hegel and Nietzsche” […]

Since I like both Nietzsche and Deleuze, must I conclude that I do not like Hegel? Or will have a hard time liking him?

Can I form my opinion based on the opinion of another person?

I should do no such thing of course.

But I could if I wanted to.

And I can trust Nietzsche when he says Plato is boring, can’t I?

.jpg)