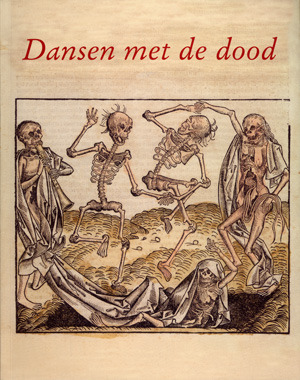

A friend lent me her copy of the book above, an excellent compendium of visuals of the perennial favourite dance of death theme. Dansen met de Dood is a Dutch language book on the iconography of dance of death by Johan De Soete, Harry Van Royen and Dirk Vanclooster. Dance of Death, also variously called Danse Macabre (French), Danza Macabra (Italian) or Totentanz (German), is a late-medieval allegory on the universality of death: no matter one’s station in life, the dance of death unites all. La Danse Macabre consists of the personified death leading a row of dancing figures from all walks of life to the grave—typically with an emperor, king, pope, monk, youngster, beautiful girl, all skeletal. They were produced to remind people of how fragile their lives were and how vain the glories of earthly life were. Its origins are postulated from illustrated sermon texts; the earliest artistic examples are in a cemetery (Cimetière des Innocents) in Paris from 1424.

The book was based on a 2008 exhibition in the Flemish city of Koksijde. It featured manuscripts of the Great Seminary in Bruges and the Catharijne convent in Utrecht, objects and graphic work by Wim Delvoye, Pierre Alechinsky, Paul Delvaux, Frans Masereel, James Ensor, Käthe Kollwitz, Félicien Rops and Hans Holbein.

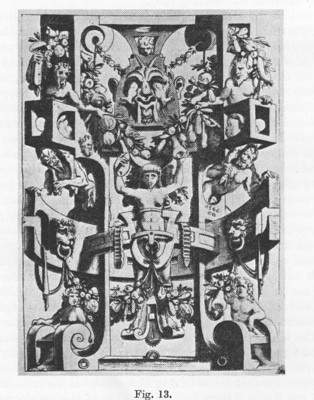

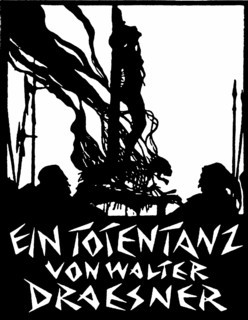

The images below were new to me.

Walter Draesner Ein Totentanz, nach Scherenschnitten von Walter Draesner mit Geleitwort von Max von Boehn(1922). With a preface by Max von Boehn