The Jamnitzers were a family of goldsmiths who lived in the 16th century. They worked for very rich people and filled the ‘Schatzkammer‘ of Northern Europe with highly luxurious items, fuelling the general economy.

However, it is their works on paper which interest us here.

First there is the father, Wenzel Jamnitzer (1507/08 – 1585). He is the author of Perspectiva Corporum Regularium (1568), a fabulous work on perspective and geometry. Of special interest in the Perspectiva is a series of architectural fantasies of spheres[1], cones[2] and tori[3].

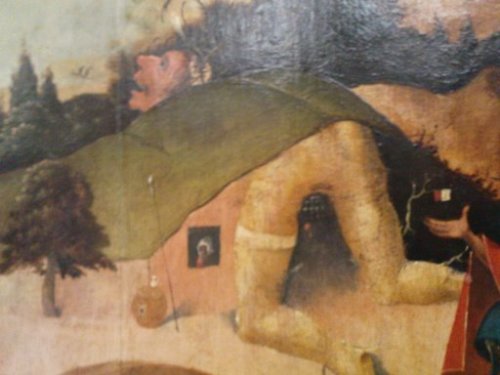

Second there is the grandson, Christoph Jamnitzer (1563–1618). Where his grandfather favoured mathematical precision and the sounding voice of reason, the grandson, author of Neuw Grottessken Buch (1610), favoured sweeping curvilinearity, abject grotesqueries and feasts of unreason. The most famous print of Neuw Grottessken Buch is the Grotesque with two hybrid gristly creatures, shown left.

If you see the work of grandfather and grandson side by side, both Jamnitzers seemed to have been plagued by the sleep of reason, the grandfather suffering from nightmares of abandonment and the grandson challenged by nightmares of being overwhelmed by the dark forces of nature.