Writing Degree Zero (Le Degré zéro de l’écriture, 1953) is book-length essay written by Roland Barthes. It was published in English by Hill and Wang in 1968. Its current edition features a foreword by Susan Sontag and was translated by Annette Lavers and Colin Smith. It introduced the literary term écriture to Anglophone literary theory.

Category Archives: French culture

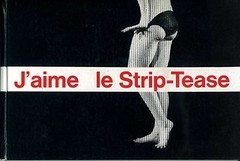

J’aime le striptease

“J’aime le Strip-Tease” by Franck Horvat

Via Zines, a lovely series of portraits of nobrow strip-teaseuse Rita Renoir, the tragedienne of strippers.

This post is Eye Candy #14

Brigitte Bardot and music (wmc #35 and 36)

Brigitte Bardot photographed by Michel Bernanau in 1968

Brigitte Bardot participated in various musical shows and recorded many popular songs in the 1960s and 1970s, mostly in collaboration with Serge Gainsbourg, Bob Zagury and Sacha Distel, including “Harley Davidson”[1], “Je Me Donne A Qui Me Plait“[2], “Bubble gum“[3], “Contact“[4], “La bise aux hippies”[5], “Je Reviendrais Toujours Vers Toi“[6], “L’Appareil A Sous[7]“, “La Madrague[8]“, “On Demenage“, “Sidonie“, “Je danse donc je suis”[9] “Tu Veux, Ou Tu Veux Pas?“, “Le Soleil De Ma Vie“[10] (the cover of Stevie Wonder‘s “You Are the Sunshine of My Life“) and notorious “Je t’aime… moi non plus“.

Click the numbers to listen to the tracks.

“Je t’aime moi non plus”, which I’ve mentioned here, is World Music Classic #35, and the philosophical “Je danse donc je suis”[9] (I dance therefore I am) is World Music Classic #36.

What is philosophy, or, when there is no longer anything to ask

Unidentified photo of see also Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari

“The question [What Is Philosophy?] can perhaps be posed only late in the life, with the arrival of old age and the time for speaking concretely…It is a question posed in a moment of quiet restlessness, at midnight, when there is no longer anything to ask. It was asked before; it was always being asked, but too indirectly or obliquely; the question was too artificial, too abstract. Instead of being seized by it, those who asked the question set it out and controlled it in passing. They were not sober enough. There was too much desire to do to wonder what it was, except as a stylistic exercise. That point of nonstyle where one can finally say, “What is it I have been doing all my life?” had not been reached. There are times when old age produces not eternal youth but a sovereign freedom, a pure necessity in which one enjoys a moment of grace between life and death, and in which all the parts of the machine come together to send into the future a feature that cuts across all ages…”–Qu’est-ce que la philosophie? (1991). Trans. What Is Philosophy? (1996).

World music classic #34

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=perVFDDy_xg&]

“Theme De Yo Yo” is a musical composition by American jazz band Art Ensemble of Chicago with vocals by Fontella Bass. The composition was part of the soundtrack to the 1971 French film Les Stances à Sophie and was first compiled on the 1995 Soul Jazz Records free jazz compilation Universal Sounds Of America.

AEOC recorded this album when they were staying in Paris in the early 1970s. Did they also record at that time “Comme à La Radio” (Brigitte Fontaine; Areski)?

Words to describe the track are: fierce.

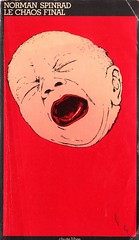

Introducing French imprint Chute Libre

This post is part of the cult fiction series, this issue #4

Norman Spinrad on French collection Chute Libre

Chute Libre is/was a French publishing imprint directed by Gérard Leibovici. They published, amongst others, the translated work of the new wave of science fiction authors Philip José Farmer, Norman Spinrad, Michael Moorcock, Roger Zelazny and Theodore Sturgeon.

I can’t remember who I had this conversation with, but the conclusion was that “we” could not find the illustrator of this beautiful series (follow the link to the source post to find some succulent tentacle erotica), so if anyone knows who was behind these designs, please let “us” know.

Norman Spinrad provided the inspiration for the name Heldon, French guitarist Richard Pinhas‘s band (which to me is the bit the French equivalent to Sonic Youth, but 10 years sooner). The name of the band was taken from Spinrad’s 1972 novel The Iron Dream.

Chute libre is French for free fall.

Via bxzzines, see also English-language covers posted by John Coulthart and all the covers in one handy place by Mike.

Statues also die

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5Pb9nykjQA]

Les Statues meurent aussi (Eng: Statues also Die) is a short subject documentary film by Chris Marker and Alain Resnais released in 1953 and financed by the anticolonial organisation Présence africaine. Its theme was that Western civilization is responsible for the decline of black art due to cultural appropriation. The film was seen at the Cannes Film Festival, it won the Prix Jean Vigo in 1954 but was banned shortly afterwards for more than 10 years by the French censor.

Aimé Césaire (1913 – 2008)

Aimé Fernand David Césaire (25 June 1913 – 17 April 2008) was a French poet, author and politician. He was with Léopold Sédar Senghor one of the figure heads of the négritude movement, the precursor to the Black Power movement of the 1960s. His writings reflect his passion for civic and social engagement. He is the author of Discours sur le colonialisme (Discourse on Colonialism) (1953), a denunciation of European colonial racism which was published in the French review Présence Africaine. In 1968, he published the first version of Une Tempête, a radical adaptation of Shakespeare’s play The Tempest for a black audience.

Erutarettil, or, Treasures from the Antwerp library

I went to the Permeke library in the center of Antwerp yesterday evening and loaned these:

- Les Symbolistes (Serge Baudiffier; Jean-Marc Debenedetti , 1990)

- Sade / Surreal

- Ghislaine Wood’s Art Nouveau and the Erotic

- Owen S. Rachleff ‘s The Occult in Art

- William Rubin ‘s Primitivism in 20th Century Art

Two of these books I had already loaned, the work by Rachleff, which is excellent, and the sublime Sade / Surreal, which I’ve mentioned before here. Sade/Surreal is a pricey book (a French bookseller currently wants more than 300 EUR for it, but a German vendor is currently letting it go for less than 40 Euros, which is a bargain, if you have deep pockets, consider buying it for me as a present). For the last hour of so, I’ve been updating my wiki with the names found on the opening and closing pages of the book (pictured below), which reads like a who’s who of Sadean thought, a summa sadeica, as it were.

Opening and closing page of Sade/Surreal

There were only a couple of names I could not identify, any help is welcome: Retz (either Gilles de Rais, or the cardinal with the same name, Young (perhaps Mr. Young of Night Thoughts?), de Saint Martin, Bertrand (probably Aloysius Bertrand ?) and Constant (Constantin Meunier?). The rest is indentified.

Also in the same book is the engraving below, which I find lovely, like a cake-building or a building of collapsing blubbery wet clay.

Tomb of Pompeii by Jean-Baptiste Tierce, 1766

Cult fiction #3

I started reading Verschijningen today, a Dutch translation of a selection of texts by Henri Michaux, published by Meulenhoff in 1972.

My first conscious exposure to the thought of Michaux was by way of David Toop‘s Ocean of Sound, in which Toop describes Michaux as an armchair traveler.

The collection comprises Les poètes voyagent (1946); Un certain Plume (1930); Apparitions (1946); Ici Poddema (1946); texts from Façons d’endormi, facons d’eveille; followed by a short essay by the translator Laurens Vancrevel.

My first impressions are based on reading Les poètes voyagent; Un certain Plume and Apparitions, Plume providing the most satisfying reading experience: the whole of Plume breathes Edgar Allan Poe and especially Poe’s incomparable short story Loss of Breath.

Keywords of Michaux’s writing are viscerality; the tropes of the macabre, fantastique, rocambolesque and grotesque; petrifaction, death, the void, lightness and emptiness, “everything-you-know-is-wrong” feelings, disintegration, decapitation and dismemberment, walls (and especially ceilings). All things considered, this is a very eerie collection told in a matter of fact voice.

If the content and tone are definitely Poe, the form of this collection’s most likely sibling is the writing of Baudelaire, and especially Baudelaire’s prose poetry.

The “liner notes” to this collection also alerted me to Images du monde visionnaire, a film by Eric Duvivier and Henri Michaux, an educational film which was produced in 1963 by the film department of Swiss pharmaceutical company Sandoz (best known for synthesizing LSD in 1938) in order to demonstrate the hallucinogenic effects of mescaline and hashish. It is the only venture in film of notable French writer and painter Henri Michaux. See that film by following the Documents entry, read more at Ombres Blanches.