I spent the day in London yesterday. I arrived at St Pancras railway station, headed for the University of London in Russell Square where there was a day on political myth and Hans Blumenberg. I skipped class and went to the National Gallery and saw:

Lady Standing at a Virginal by Johannes Vermeer, detail

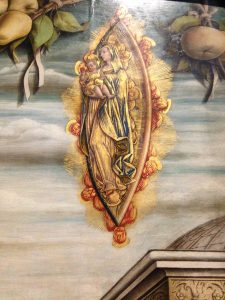

The Vision of the Blessed Gabriele by Carlo Crivelli (left, the yoni detail), right other detail.

Witches at their Incantations by Salvator Rosa, full and cooking hag detail

Two Followers of Cadmus devoured by a Dragon by Cornelis van Haarlem, detail

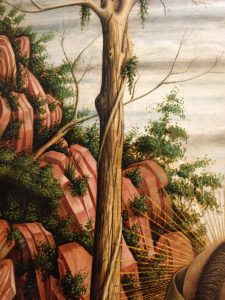

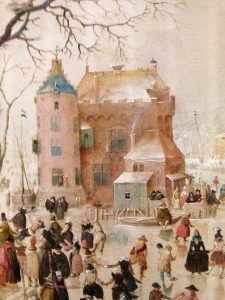

Forgotten which this one is, I was quite impressed by it, I think it’s Dutch, detail

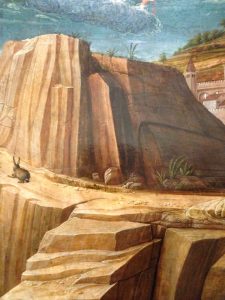

The Agony in the Garden by Andrea Mantegna, detail

The Fight between the Lapiths and the Centaurs by Piero di Cosimo, detail

The Death of Procris by Piero di Cosimo, detail

Meeting Place of the Hunt by Adolphe Joseph Thomas Monticelli, detail

Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway by J. M. W. Turner, detail

Forgot, probably a Jupiter and Antiope, I loved the way the nipple was pinched, detail

Portrait of the Artist’s Wife, Cunera van der Cock by Frans van Mieris the Elder, very small and delicate painting, this one.

The Ugly Duchess by Quentin Matsys, cleavage detail

The Agony in the Garden by Bellini, detail of village in the distance

A Scene from El Hechizado por Fuerza (‘The Forcibly Bewitched’) by Francisco Goya, apparently a portrait of Charles II of Spain, detail

Still Life with a Nautilus Cup by Gerrit Willemsz. Heda, detail