Antonin Artaud’s radiophonic play ‘To Have Done With the Judgment of god‘.

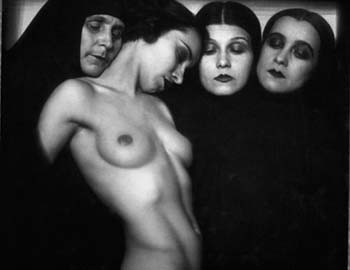

This work was shelved by Wladimir Porché, the director of the French Radio, the day before its scheduled airing on February 2, 1948. The performance was prohibited partially as a result of its scatological, anti-American, and anti-religious references and pronouncements, but also because of its general randomness, with a cacophony of xylophonic sounds mixed with various percussive elements. While remaining true to his Theater of Cruelty and reducing powerful emotions and expressions into audible sounds, Artaud had utilized various, somewhat alarming cries, screams, grunts, onomatopoeia, and glossolalia.

Artaud coined the term body without organs in this radio play.

Two excerpts and the full text here.

- “I deny baptism and the mass. There is no human act, on the internal erotic level, more pernicious than the descent of the so-called jesus-christ onto the altars.

- No one will believe me and I can see the public shrugging its shoulders but the so-called christ is none other than he who in the presence of the crab louse god consented to live without a body…”

- …

- All this is very well,

but I didn’t know the Americans were such a warlike people.

In order to fight one must get shot at

and although I have seen many Americans at war

they always had huge armies of tanks, airplanes, battleships

that served as their shield.

I have seen machines fighting a lot

but only infinitely far

behind

them have I seen the men who directed them.

Rather than people who feed their horses, cattle, and mules the

last tons of real morphine they have left and replace it with

substitutes made of smoke,–Artaud via [1]