John Calvin @500

Calvinism has been known at times for its simple, spartan and unadorned churches and lifestyles, as depicted in this painting by Emmanuel de Witte. Belgium, where I live, is on the Protestant-Catholic border between Northern and Southern Europe. The South is known for its joie de vivre, haute cuisine and exuberance, the North for its antithesis: frugality, meager food and general restraint.

John Calvin né Jean Cauvin (10 July 1509 – 27 May 1564) was an influential French theologian and pastor during the Protestant Reformation. He was a principal figure in the development of the system of Christian theology later called Calvinism. Originally trained as a humanist lawyer, he suddenly broke from the Roman Catholic Church in the 1520s. After religious tensions provoked a violent uprising against Protestants in France, Calvin fled to Basel, Switzerland, where in 1536 he published the first edition of his seminal work Institutes of the Christian Religion.

In the 1540s the Frenchman John Calvin founded a church in Geneva which forbade alcohol and dancing, and which taught God had selected those destined to be saved from the beginning of time. His Calvinist Church gained about half of Switzerland and churches based on his teachings became dominant in the Netherlands (the Dutch Reformed Church) and Scotland (the Presbyterian Church).

Anyone against him was called a Libertine, providing the origins of a well-loved term of this blog. The group of Libertines was led by Ami Perrin and argued against Calvin’s “insistence that church discipline should be enforced uniformly against all members of Genevan society”. By 1555, Calvinists were firmly in place on the Genevan town council, so the Libertines, led by Perrin, responded with an “attempted coup against the government and called for the massacre of the French … This was the last great political challenge Calvin had to face in Geneva.

Engraving of the Iconoclasm from G. Bouttat (1640-1703)

Many Protestant reformers including John Calvin were against religious art by invoking the Decalogue’s prohibition of idolatry and the manufacture of graven images of God. As a result, statues and images were damaged in spontaneous individual attacks as well as unauthorised iconoclastic riots. In my part of the world, this started in 1566, two years after Calvin’s death and resulted in the Beeldenstorm.

Calvin’s legacy in modern times has produced a variety of opinions. Certainly the execution of Servetus has left a negative view of Calvin. Voltaire mentions the event in his Poème sur la loi naturelle (Poem on Natural Law, 1756) and Dialogues chrétiens (Christian Dialogues, 1760). For Voltaire, Calvin’s philosophy had not produced any improvement over the intolerance presented in previous revealed religions. Calvin is discussed in Max Weber’s classic work on the The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism in which he argues that Calvin’s teachings provided ideological impetus for the development of capitalism. Political historians have recognised his contributions to the development of representative democracy in general and the American system of government in particular.

In find Calvin only mildly interesting, more radical Reformation info can be found under the headings of Thomas Müntzer, Jan Hus, the anabaptists and the Peasants’ War.

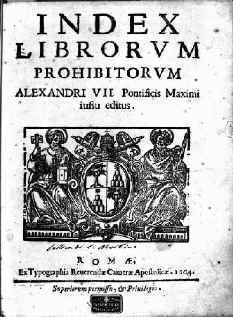

As was to be expected, John Calvin‘s writing was put on one of the more interesting compendiums of Western literature, The Index.

The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (1824) – James Hogg [Amazon.com] [FR] [DE] [UK]

Illustration by William Blake.

If you’d like to know more about religious fanaticism and the intricacies of Protestantism, I can recommend James Hogg‘s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner (by way of Lichanos).

see also Calvinism, 16th century Europe, Northern Renaissance, Protestant work ethic, iconoclasm

-