Lev Kuleshov, Russian filmmaker and film theorist @110

For Kuleshov (1899 – 1970), the essence of the cinema was editing, the juxtaposition of one shot with another. To illustrate this principle, he created what has come to be known as the Kuleshov Experiment. In this now-famous editing exercise, shots of an actor were intercut with various meaningful images (a casket, a bowl of soup, and so on) in order to show how editing changes viewers’ interpretations of images.

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=grCPqoFwp5k&]

Kuleshov Experiment

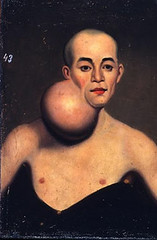

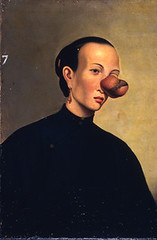

Kuleshov edited together a short film in which a shot of the expressionless face of Tsarist matinee idol Ivan Mozzhukhin was alternated with various other shots (a plate of soup, a girl, an old woman’s coffin). The film was shown to an audience who believed that the expression on Mozzhukhin’s face was different each time he appeared, depending on whether he was “looking at” the plate of soup, the girl, or the coffin, showing an expression of hunger, desire or grief respectively. Actually the footage of Mozzhukhin was the same shot repeated over and over again. Vsevolod Pudovkin (who later claimed to have been the co-creator of the experiment) described in 1929 how the audience “raved about the acting…. the heavy pensiveness of his mood over the forgotten soup, were touched and moved by the deep sorrow with which he looked on the dead woman, and admired the light, happy smile with which he surveyed the girl at play. But we knew that in all three cases the face was exactly the same.”

Kuleshov used the experiment to indicate the usefulness and effectiveness of film editing. The implication is that viewers brought their own emotional reactions to this sequence of images, and then moreover attributed those reactions to the actor, investing his impassive face with their own feelings.

The effect has also been studied by psychologists, and is well-known among modern film makers. Alfred Hitchcock refers to the effect in his conversations with François Truffaut, using actor James Stewart as the example (although Hitchcock mistakes Kuleshov with Pudovkin).

The experiment itself was created by assembling fragments of pre-existing film from the Tsarist film industry, with no new material. Mozzhukhin had been the leading romantic “star” of Tsarist cinema, and familiar to the audience.

Kuleshov demonstrated the necessity of considering montage as the basic tool of cinema art. In Kuleshov’s view, the cinema consists of fragments and the assembly of those fragments, the assembly of elements which in reality are distinct. It is therefore not the content of the images in a film which is important, but their combination. The raw materials of such an art work need not be original, but are pre-fabricated elements which can be disassembled and re-assembled by the artist into new juxtapositions.

The montage experiments carried out by Kuleshov in the late 1910s and early 1920s formed the theoretical basis of Soviet montage cinema, culminating in the famous films of the late 1920s by directors such as Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Pudovkin and Dziga Vertov, among others. These films included The Battleship Potemkin, October, Mother, The End of St. Petersburg, and The Man with a Movie Camera.

Soviet montage cinema was suppressed under Stalin during the 1930s as a dangerous example of Formalism in the arts, and as being incompatible with the official Soviet artistic doctrine of Socialist Realism.

Here is Hitchcock explaining the Kuleshov effect:

[Youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hCAE0t6KwJY]

Alfred Hitchcock

See also: continuity editing, shot reverse shot.