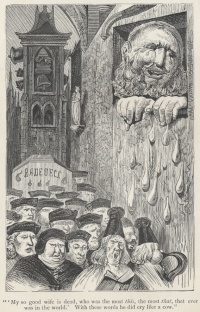

“I go to seek a Great Perhaps“, supposed last words of Rabelais

I finished reading Mikhail Bakhtin’s Rabelais and His World (1965) and took notes here.

“Our study is only a first step in the vast task of examining ancient folk humor” says Bakhtin on the last page of his monumental work. To me, this was not a first step, but a pretty comprehensive overview of Rabelais, his language and his time. Sometimes I even felt there was just a bit too much repetition.

What I will most likely remember best of Bakhtin’s analysis is the metaphor of the pregnant death: symbol for a number of processes characterized by the prefix re-: renewal, rebirth, regeneration, reconstruction, revitalization and ultimately Renaissance.

I find myself smiling and nodding in admiration simultaneously when reading Rabelais.

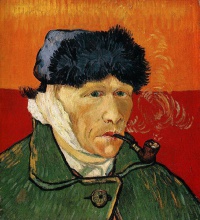

Spain had Cervantes, England had Shakespeare, but the Frenchmen Rabelais was the father of them all.

When he died, he said “I go to seek a Great Perhaps“.

Did he?

Nobody knows, actually.

More and more I am confronted with the spuriousness of attributions.

.jpg)