Françoise Arnoul was a French actress known for her parts in French Cancan, The Devil and the Ten Commandments and Forbidden Fruit; and not so much for her part in Post Coitum, Animal Triste (1997). However, I show you the trailer of that film, because of its title, which I have been able to trace into the 16th century, in the work of Jean Benedict in La somme des péchés et le remède d’iceux (1595).

Tag Archives: 1931

RIP Eddy Posthuma de Boer (1931 – 2021)

Eddy Posthuma de Boer was a Dutch photographer.

RIP Johanna Fürstauer (1931 – 2018)

Johanna Fürstauer was an Austrian writer.

By reading Jan Verplaetse’s “Vrouwenpijn en mannenplezier: de antifeministische wortels van sadomasochisme in de Belle Epoque” (1999), I came across Johanna Fürstauer, an Austrian writer who specialized in Sittengeschichte, a famous German euphemism for histories of the vita sexualis. Fürstauer is from the same sex researching generation as Eberhard and Phyllis Kronhausen.

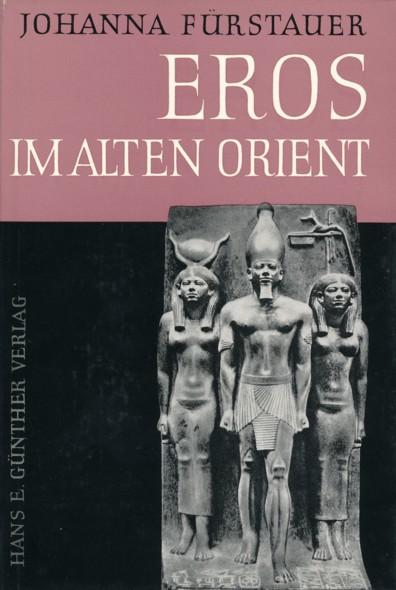

Above is a picture of the cover of Eros im alten Orient (1965) on Eastern erotica, the debut of Fürstauer.

RIP Nawal El Saadawi (1931 – 2021)

Nawal El Saadawi was an Egyptian feminist writer, activist, physician, and psychiatrist.

She wrote many books on the subject of women in Islam, paying particular attention to the practice of female genital mutilation in her society.

She described her mutilation in The Hidden Face of Eve (1977) in these words:

“Then suddenly the sharp metallic edge seemed to drop between my thighs and there cut off a piece of flesh from my body.”

[…]

“I did not know what they had cut off from my body, and I did not try to find out. I just wept, and called out to my mother for help. But the worst shock of all was when I looked around and found her standing by my side. Yes, it was her, I could not be mistaken, in flesh and blood, right in the midst of these strangers, talking to them and smiling at them, as though they had not participated in slaughtering her daughter just a few moments ago.”

RIP Jean-Claude Carrière (1931 – 2021)

Jean-Claude Carrière was a French novelist and screenwriter famous for scripting The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, The Phantom of Liberty and The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

I give you the toilet scene from The Phantom of Liberty, it makes you wonder if Buñuel scripted it alone or he asked Carrièret to assist him.

RIP John le Carré (1931 –2020)

Every once and a while somebody dies and his or her death makes you reconsider what you know of the deceased.

Such was the case with John le Carré (1931 –2020). At first I thought he was just another spy fiction writer and that my relationship to him was probably nothing.

I found the opening lines of The Spy Who Came in From the Cold and found them appealing, put them on my encyclopedia but I still did not know what to post on my blog.

Then I read that the recurring Smiley character was a sort of anti-hero but most of all an anti-James Bond, badly dressed, bald, overweight, bespectacled, unattractive. With a wife that cheats on him more than once. Also with a Russian spy.

And then today, in my local press, I read Marc Reynebeau (born 1956):

“If the setting of Le Carré’s work changed after the Cold War, his theme remained. This is anchored in a pronounced skepticism about institutions and the corrupting effect that is inherent in every institutional dynamic.”

Two things.

One.

The corruption. “Power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” said John Emerich Edward Dalberg-Acton. There is no escaping the corrupting power of power.

Two.

Skepticism about institutions. I recently read Paul Collier and he put me on to this. It’s fairly obvious, but somebody needed to point it out. There are two kinds of societies. Societies with high level of trust and societies with low level of trust.

The former develop.

The latter stall. For example, Collier says in Exodus: How Migration Is Changing Our World (2013):

“It is not possible for Nigerians to get life insurance. This is because, given the opportunism of the relevant professions, a death certificate can be purchased without the inconvenience of dying.”

And then, diggin deeper still, one founds an interview of le Carré which shows him critical of consumerism that makes you wonder whether Michel Clouscard was awareof it:

“I dislike Bond. I’m not sure that Bond is a spy. I think that it’s a great mistake if one’s talking about espionage literature to include Bond in this category at all. It seems to me he’s more some kind of international gangster with, as it is said, a license to kill… He’s a man entirely out of the political context. It’s of no interest to Bond who, for instance, is president of the United States or of the Union of Soviet Republics. It’s the consumer goods ethic, really, that everything around you, all the dull things of life, are suddenly animated, by this wonderful cachet of espionage. With the things on our desk that could explode, our ties that could suddenly take photographs. These give a drab and materialistic existence a kind of magic.”–John le Carré interviewed by Malcolm Muggeridge, first broadcast on February 8, 1966, 16:45

RIP John le Carré

RIP Nelly Kaplan (1931 – 2020)

Argentina-born French writer and filmmaker Nelly Kaplan died in Geneva. She turned 89.

She taught, wrote, assisted Abel Gance and directed her own films.

She is best known for a 1969 film, La Fiancée du pirate, “the pirate’s sweetheart”. You can see large parts of that film in a documentary by Zo Anima (they make quite interesting documentaries about film history) that mainly talks about the feminist and witch-like aspects of that film.

But also, it would seem, YouTube has the entire film online:

Kaplan also wrote and directed two film documentaries about artists’ lives, a genre that is barely practiced today. Those artist films are Gustave Moreau (1961) and Rodolphe Bresdin (1962). If I am not mistaken, Moreau has his own museum in Paris, just like Wiertz in Brussels, with whom Moreau bears similarities, Moreau was the better painter.

The opening credits of Gustave Moreau states that quotations from the oeuvre of Breton, Huysmans, Racine, Jarry, Lautréamont and Baudelaire can be expected.

RIP Nelly Kaplan.

RIP John Fraser (1931 – 2020)

John Fraser was a Scottish actor known for The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960) and Repulsion (1965).

My gaydar was effective, I noticed while watching The Trials of Oscar Wilde that Fraser was gay. It’s good that they cast a gay man for a gay part in 1960.

In Repulsion too, Fraser has that gay, slightly decadent and perverse persona.

RIP Michael Lonsdale (1931 – 2020)

Michael Lonsdale was a British-French actor who mainly worked in France, one of my favorite actors. He played in many films, though rarely as the protagonist. He turned 89.

In the English-speaking world, he was known for his role as the villain Hugo Drax in the James Bond film Moonraker, and for his appearances in The Day of the Jackal and The Remains of the Day.

As a character actor with a penetrating gaze, he can be admired in auteur films such as Le fantôme de la liberté (1974) by Luis Buñuel, Glissements progressifs du plaisir (1974) by Alain Robbe-Grillet and the unforgettable 5×2 (2004) by François Ozon.

I would like to take this rather sinister opportunity to highlight the story “Bartleby” (1853) by Herman “Moby Dick” Melville. That short story was adapted for film four times, and in the 1976 French version, Lonsdale plays the bailiff.

The hero in “Bartleby” is called Bartleby. He is a clerk who is recruited at a law firm to copy documents, but soon after his arrival at the firm refuses an assignment with the legendary words “I would prefer not to”. From then on, Bartleby the clerk basically refuses everything, which means that he refuses to live.

This hero is reminiscent of other impossible, frustrated novel characters such as the nameless hero in Dostoevsky’s Notes from the Underground (1864) and Julien Sorel in Stendhal’s The Red and the Black (1830).

In the clip, Lonsdale visits Bartleby in prison where he urges the latter to make a last effort to live. In vain. We see Bartleby die while standing up.

RIP Lucia Bosè (1931 – 2020)

Lucia Bosè was an Italian actress with a long and fruitful career.

I choose to remember her by a documentary film she did not act in.

In Toute la mémoire du monde (1956), an identified photo of her is on the cover of a fictional book with the title Mars.

The cover of that book is unveiled at 9:42. The audience follows the book around the library as it makes its way to the shelves.