Tag Archives: grotesque

On the originary date of ‘Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe’

Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe by Eugène Bataille (Sapeck) (page from the book Le rire, source Gallica.bnf.fr)

I’ve been fascinated by the Incoherents since I first stumbled upon them in 2007[1][2].

After becoming a member of the Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp library some weeks ago, I have been able to consult two seminal books on that movement’s history: the Arts incoherents, academie du derisoire exhibition catalog (1992) by Luce Abélès/Catherine Charpin and The Spirit of Montmartre: Cabarets, Humor and the Avant-Garde, 1875-1905 (1996) by Phillip Dennis Cate.

Object of my research was to check the dates of works I consider canonical to the proto-avant-garde, dates which I previous held to be the neat series of 1882, 1883 and 1884.

It’s a pity, but I’ve had to adjust that series to 1882, 1883 and 1887: Negroes Fighting in a Tunnel at Night (1882), Funeral March for the Obsequies of a Deaf Man (1884) and Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe (1887).

According to my research, Mona Lisa Smoking a Pipe by Sapeck, which is still listed over at Wikipedia as originating in 1883 and erroneously titled as Le rire, in fact first saw the light of day in 1887, in the book Le Rire by Coquelin cadet.

Wikipedia is not the only reference work in error. The Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines erroneously states that this Mona Lisa was first shown in 1883 at the second “Incohérents” exhibition.

What is the importance of this augmented Mona Lisa?

Simple.

Perhaps the invention of high art with capital ‘A’ coincided with the first blows of its ridicule. This augmented Mona Lisa was a desecration, a violation, a rape of its masterpiece: the Mona Lisa proper by da Vinci.

Think about it.

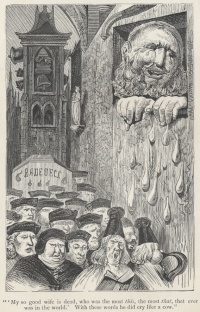

The gaping mouths of Goya

Los Chinchillas from Los Caprichos by Francisco de Goya

I’m reading Rabelais and His World and I’m taking notes as I go along.

There is much repetition of the tropes of Rabelais in Bakhtin’s book. For example, the term dismemberment is mentioned about twenty times and gaping about ten times. The grotesque body and what it stands for is explained over and over again.

It suddenly occurred to me that Francisco Goya is the specialist of the gaping mouth.The mouth which is wide open. Incidentally, gaping means yawning in my language (Dutch).

This morning I looked up the combination Goya/gaping/mouth.

British art critic David Sylvester came to the same conclusion:

- “The mouth plays a role in Goya‘s art more prominent than in that of any other major artist. Mouths leer, grin, gape, gasp, moan, shriek, belch. A hanged man’s mouth lies open and a woman reaches up to filch his teeth. Grown men stick fingers in their mouths like sucking infants. Mouths vomit, the sick gushing out of them, and a great furry beast sicks up a pile of human bodies. Mouths guzzle: they guzzle avidly, ferociously, living flesh as well as dead. Saturn grips one of his children in his fists and with his mouth tears him limb from limb.”

One can add to this the Lazarillo painting and the Caprichos There Is Plenty to Suck, Ya es hora, Estan calientes and the force-fed Chinchillas. And from the Desastres: the vomiting man in Para eso habeis nacido and the vomiting monster of Fiero Monstruo!

I am a god in the deepest core of my thoughts

Detail of A Pilgrimage to San Isidro (1819–23) by Francisco de Goya

I’m a stickler for firsts and origins, almost childishly so, or at least obsessively.

While researching Goya I stumbled on a letter by Goya to Bernardo de Iriarte dated January 4, 1794, in which I read:

I have devoted myself to painting a group of pictures in which I have succeeded in making observations for which there is normally no opportunity in commissioned works, which give no scope for fantasy and invention.” (tr. Enriqueta Harris)

Goya’s insistence on his artistic freedom (key to the notion of “romantic originality“) in making art with ‘fantasy‘ and ‘invention‘ “for which there is normally no opportunity in commissioned works” makes this dictum one of the candidates for a Manifesto of Romanticism.

Other dicta which emphasize the egomaniac (wording by Nordau) importance the Romantics placed on untrammelled feeling is the remark of the German painter Caspar David Friedrich that “the artist’s feeling is his law” and William Wordsworth‘s ascertainment that “all good poetry is the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings“.

In the Dutch language, the poet Willem Kloos said “I am a god in the deepest core of my thoughts,” giving voice to the Romantic conception of the artist.

Goya was a god too (and perhaps the first Romantic painter) though not a god that sought to please, soothe, nor comfort.

Illustration: A Pilgrimage to San Isidro, one of the black paintings by Goya

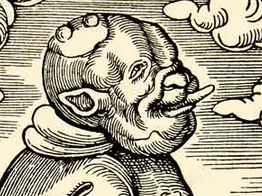

A rudimentary taxonomic vocabulary for hybrid creatures

Detail from the bottom of the central panel of Bosch’s Last Judgment in Vienna.

In my previous post[1] I mistakenly claimed that bodyhead is the term for what we Dutch-language speakers call koppoter or kopvoeter.

In reality, the term bodyhead was coined by English artist Paul Rumsey in the late 20th and early 21st century as titles to his own Two Bodyheads. A quick search in Google Books confirms this.[2]

Paul pointed me to the gryllus, a creature similar to gastrocephalic creatures (belly faces), to blemmyae and to his own bodyheads.

Gryllus, a term new to me, appears to be an interesting word, leading me to the discovery of the rudimentary taxonomy of hybrid creatures of the title of this post.

How so, you ask?

Here we go:

Gryllus (plural grylli) means pig in Greek and cricket in Latin. (Marina Warner, Monsters of Our Own Making).

In Plutarch’s Moralia, Gryllus was one of Circe’s victims who preferred to stay a pig after his transformation. This episode is known as “Ulysses and Gryllus“. Innumerable writers have commented on this episode, see “reasoning beasts”.

Another ancient writer who mentions grylli is Pliny the Elder in his Natural History. His concern is visual, i.e. painting. He uses the word gryllus for a class of grotesque figures first used in painting by Antiphilus of Alexandria: “he painted a figure in a ridiculous costume, known jocosely as the Gryllus; and hence it is that pictures of this class are generally known as “Grylli.”

The history of the grylli has received its most in-depth study in Marina Warner’s Monsters of Our Own Making. Most sources agree that the current meaning of the gryllus derives from Le moyen âge fantastique (1955) by Jurgis Baltrusaitis.[3]

The book Images, Texts, and Marginalia in a “Vows of the Peacock” by Domenic Leo gives a taxonomic vocabulary of hybrids in which the gryllus is one element:

- “I am using terminology proposed by Sandler, “Reflections on the Construction of Hybrids,” and Jurgis Baltrušaitis, Le moyen âge fantastique. The rudimentary taxonomic vocabulary for hybrids is as follows: bifurcated (head as center with two bodies), gryllus (body with no torso: head replaces genitals), pushmepullu (one body with a head emerging from each side), and composite (hybrids created from multiple parts).”

There is also this excellent Spanish-language page on grotesque grylli.[4].

RIP Jean Rustin

Jean Rustin (1928– 2013) was a French painter, and an important figurative artist.

Beginning in the early 1970s, he created a bizarre world of human figures, where an existential dead-end is transformed into fright, darkness abhorrence, without much pity nor relief.

In his own words:

“I realize that behind my artistic creation, behind the fascination for the naked body, there are twenty centuries of painting, primarily religious, twenty centuries of dead Christs, tortured martyrs, gory revolutions, massacres and shattered dreams […] I realize that history and maybe art history are engraved on the body and flesh of men.” (‘Jean Rustin : A corps perdu’[1], collected in Vanités contemporaines)

See also: 20th-century French art, art horror, bleak.

Goya: gruesome and grotesque

Once again I am reminded of “To Every Man His Chimera,” one of the darkest prose poems of Charles Baudelaire.

The previous time Baudelaire’s unlucky men came to my recollection, trudging through the dust carrying upon their backs an enormous chimera as heavy as a sack of flour or coal, was while reading Joko’s Anniversary (perhaps my finest reading experience of 2013, along with the many Cortázar’s short stories I’ve had the pleasure to read).

This time the occasion is my recent acquisition of Goya : Caprichos, Desastres, Tauromaquia, Disparates (1982, Fundación Juan March), a complete set of all the engravings by Goya.

“Look how serious they are!” is number 63 from 80 prints of the Caprichos and it depicts “two demons taking a little exercise, and riding on grotesque beasts. One demon has the head of a bird, the other of a donkey.” The pack animals, the grotesque beasts, look like bipedal donkeys with faces half human, half donkey.

Creatures with the head of a bird are frightening. The wattle!, the comb!

The reverse motif, creatures with the feet of birds, has been employed in Un priape marchant sur des pattes de coq, with a far less frightening — yes, even ludicrous — effect.

The coarsest drawings in the history of caricature

When a nose is not a nose

Napoleon III nose caricatures from Schneegans’s History of Grotesque Satire

Following my previous post on [1] the concept of the grotesque body in Bakhtin’s book Rabelais and His World (which mentions the term grotesque 91 times), I did some research on previous books Bakhtin mentions in Rabelais and His World with reference to the grotesque.

One of the authors whose name pops up most (13 times) is that of Heinrich Schneegans, author of Geschichte der grotesken Satire (1894).

Bakhtin criticizes Schneegans for failing to notice the connection between caricatures of the human nose (above) and the phallic symbolism of the human nose. Sometimes a nose it not a nose.

Anything coming out of the mouth of a ‘wise fool’

I’ve been reading up on the grotesque body, finally taking the trouble and the time to read how its ‘inventor’ Mikhail Bakhtin defined it.

Here you have it, from Rabelais and His World:

“Contrary to modern canons, the grotesque body is not separated from the rest of the world. It is not a closed, completed unit; it is unfinished, outgrows itself, transgresses its own limits. The stress is laid on those parts of the body that are open to the outside world, that is, the parts through the world enters the body or emerges from it, or through which the body itself goes out to meet the world. This means that the emphasis is on the apertures or convexities, or on various ramifications and offshoots: the open mouth, the genital organs, the breasts, the phallus, the potbelly, the nose. The body discloses its essence as a principle of growth which exceeds its own limits only in copulation, pregnancy, childbirth, the throes of death, eating, drinking, ordefecation. This is the ever unfinished, ever creating body, the link in the chain of genetic development, or more correctly speaking, two links shown at the point where they enter into each other. This especially strikes the eye in archaic grotesque”. (tr. Helene Iswolsky)

It’s quite a beautiful piece of prose. It reminds me of Deleuze and Guattari saying “there is no castration” and Sloterdijk’s genius comment on the the arse: “the arse is truly is the idiot of the family.”

See embodied cognition, body genres and body politics.

Also, anything coming out of the mouth of a ‘wise fool‘: morosophy and its mutant siblings serio ludere and spoudaiogeloion are still of great interest to yours truly.

.jpg)

.jpg)