Over the past few days I’ve been mulling over Siri Hustvedt title essay A Plea for Eros which is a rumination on the effability and ineffability of sex in connection with the Antioch Ruling. Since January 1, 2006, the Antioch College in Ohio, United States, requires students to gain consent at each stage of a sexual encounter.

Hustvedt’s essay on the unreliability and ambiguity of language in relation to sexual ethics reminded me of Georges Bataille when he said that “sex begins where speech [or words] ends”, a statement I tend to agree with.

[Youtube=http://youtube.com/watch?v=q7SNOX9W3WY]

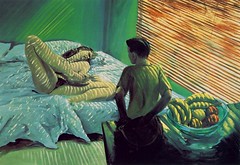

Emotionally charged scene in A History of Violence (French version)

Which brings me to Cronenberg penultimate film A History of Violence, the Straw Dogs of the 2000s. It is the story of Tom Stall, his wife Edie and their two children. Tom is a good-hearted impostor with organized crime roots. After his family finds out his true identity they initially reject him. He is finally accepted in a superb silent scene which is a celebration of the nuclear family; but not until after an emotionally charged fight between Tom and Edie followed by rough sex on the stairs. Notice the absence of adherence to the Antioch Ruling.

However, as Hustvedt points out at the beginning of her essay, an Antioch world can be full of erotic possibilities.

Imagine asking a female love interest “May I touch your left breast?”; patiently and eagerly waiting for the answer.

Dutch director Warmerdam’s cult film Little Tony predates Hustdvedt’s sentiments by 8 years. In this tragicomedy the erotic possibilities of explicitness in sexual encounters is illustrated by a key scene in which Brand, the protagonist illiterate farmer asks Lena, the school teacher who has been hired by Brand’s wife, “May I see your left breast?“. After a putative “Why?” by Lena, Brand answers: “So I can remain curious about the right one.”

History of Violence flotsam: Steven Shaviro gives a roundup of cinerati such as k-punk, girish twice, Chuck, Jodi — followed by k-punk’s reply and Jodi’s counter-reply — Jonathan Rosenbaum and his own view here.