In the history of 20th century subculture, the surreal sensibility, and Surrealism in particular takes center stage.

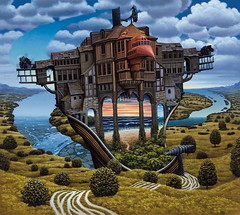

Surrealism itself deserves a decentralized and regionalized historiography.

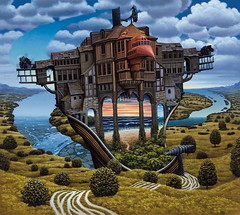

Polish surrealism for example brings the work of latter surrealist Jacek Yerka[1].

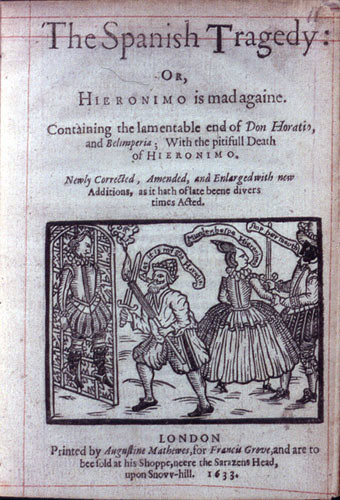

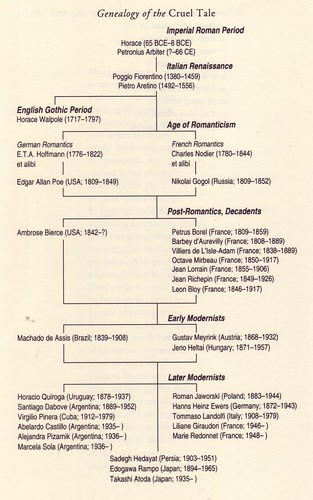

More than just a celebration of the new, Surrealism sought to find itself in the past and opened a revisionist approach to historiography. It sought to trace a sensibility in retrospect.

- Faustino Bocchi (ill. above) would have been dubbed surrealist, if Breton had known him.

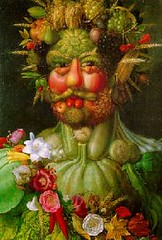

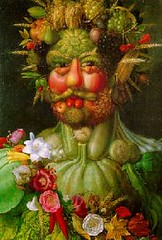

Arcimboldo (ill. above) would have been dubbed surrealist, if Breton had known him

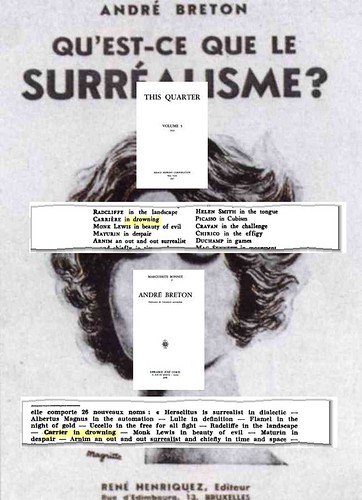

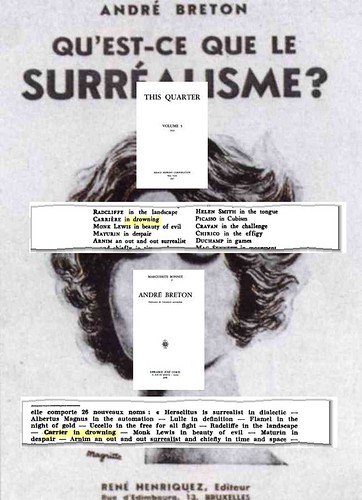

In “What is Surrealism?” Breton defines what we can label proto-Surrealism.

See the insets for the Carrier/Carrière debate

“Young‘s Night Thoughts are surrealist from cover to cover. Unfortunately, it is a priest who speaks; a bad priest, to be sure, yet a priest.

Heraclitus is surrealist in dialectic.

Lully is surrealist in definition.

Flamel is surrealist in the night of gold.

Swift is surrealist in malice.

Sade is surrealist in sadism.

Carrier is surrealist in drowning.

Monk Lewis is surrealist in the beauty of evil.

Achim von Arnim is surrealist absolutely, in space and time

Rabbe is surrealist in death.

Baudelaire is surrealist in morals.

Rimbaud is surrealist in life and elsewhere.

Hervey Saint-Denys is surrealist in the directed dream.

Carroll is surrealist in nonsense.

Huysmans is surrealist in pessimism.

Seurat is surrealist in design.

Picasso is surrealist in cubism.

Vaché is surrealist in me.

Roussel is surrealist in anecdote. Etc.”

This list comes from a lecture given by Breton in Brussels in 1934, either on May 12 or June 1 of that year, and published as a pamphlet immediately afterwards by René Henriquez, with as cover art Magritte‘s The Rape, which was created for that purpose. The enumeration in the lecture harks back to a list published in the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924.

Other versions exist, one was published in the “Surrealist Number” of This Quarter. Another version was translated to Czech and published as “Co je surrealismus?” (1937), with a cover by Karel Teige. This list reprised the 1924 version.

Many of the names on the list are obscure, but I have managed to track all … but one.

When Breton says “Carrier is surrealist in drowning,” I have no idea who he means. Apparently, I am not the only one.

Marguerite Bonnet says in the 1975 André Breton: naissance de l’aventure surréaliste

- … “Nous n’avons pas encore retrouvé le texte français de cet article, dont la version anglaise donne au « nom « Carrière » que Breton a corrigé en Carrier”

- … “We have been unable to find the French text of this article, of which the English version gives as name Carrière, which Breton later correct as Carrier”

If Bonnet confesses that she could not find the French text (published by René Henriquez) there is even more room for confusion. The “Surrealist Number” (1932) of Parisian “little magazine” This Quarter‘ (edited by Edward W. Titus)[2]; and André Breton: naissance de l’aventure surréaliste [3] each mention additional names such as Helen Smith (surrealist in tongue), Uccello (in the free for all fight), Radcliffe (in the landscape), Maturin (in despair); and can’t agree on the spelling Carrière/Carrier.