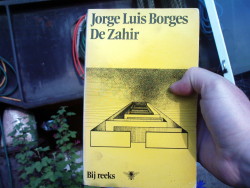

I’m currently reading De Zahir.

One sentence in “The Garden of Forking Paths” by Jorge Luis Borges caught my attention.

“I remembered too that night which is at the middle of the Thousand and One Nights when Scheherazade (through a magical oversight of the copyist) begins to relate word for word the story of the Thousand and One Nights, establishing the risk of coming once again to the night when she must repeat it, and thus on to infinity…”

Marina Warner in Stranger Magic points to “Readings and Re-Readings of Night 602” by Evelyn Fishburn which identifies the night Borges refers to as the “Tale of the Two kings and the Wazir’s Daughters“.

“By Allah, this story is my story and this case is my case,” shouts the king when he finds out that Scheherazade is telling him his frame tale.

Again in the words of Borges (from “Magias parciales del Quijote“) in which he calls that night a “magic night among the nights”:

“The King hears his own story from the Queen’s mouth. He hears the beginning of the story, which embraces all the others as well as – monstrously – itself. Does the reader really understand the vast possibilities of that interpolation, the curious danger – that the Queen may persist and the Sultan, immobile, will hear forever the truncated story of A Thousand and One Nights, now infinite and circular?”[1]

This passage illustrates the concepts of infinite regress, the Droste effect and metafiction.

.jpg)